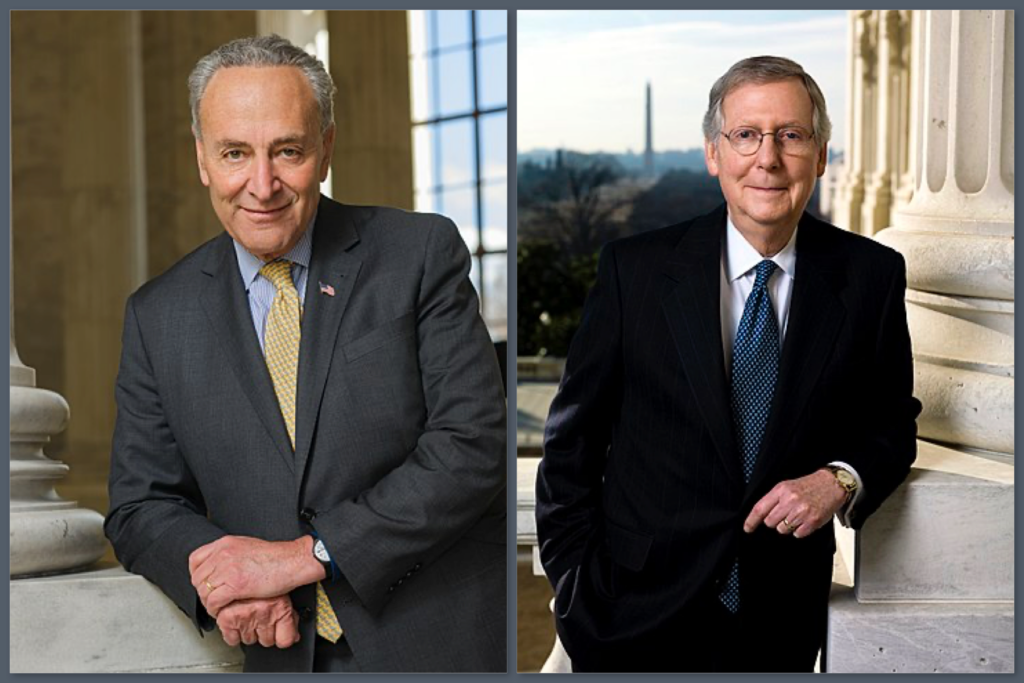

For the second time this year, Congress has been faced with the prospect of the government defaulting on its debts as the Treasury has come up against the Federal debt ceiling. No one doubts that the government should not default, yet the two parties have been bitterly divided on how to increase the debt limit. After months of disagreements, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and Republican Leader Mitch McConnell have found a strange new one-time workaround to avoid both the filibuster and a default on the government’s debts. As a result, they have also reminded the country of the importance of minority buy-in in the Senate.

Legislation to increase or suspend the debt limit can be filibustered, and it takes a supermajority of Senators to end debate via the cloture process. (Unanimous consent to shorten debate is also possible, though that requires that no one objects.)

Republicans, led by McConnell, have drawn a hard line on increasing the debt limit, insisting that it’s the majority’s responsibility, especially given the Biden Administration’s increases in Federal spending. For much of this year, they’ve insisted that the Democrats use reconciliation legislation, which cannot be filibustered. By having the Democrats use reconciliation, no Republican would need to vote for cloture. The Democrats didn’t bite on reconciliation, as it would have required amending the budget resolution and could have been a lengthy process and filled with potentially embarrassing, politically difficult amendments.

Politically difficult amendments and red lines over reconciliation can be negotiated. Failing to lift the debt limit and allowing a default on the government debt cannot. So, Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and Leader McConnell worked out a deal to circumvent the impasse, creating a one-time procedure that will be used to enact a debt limit increase, without the possibility of a filibuster.

According to this procedure, by December 31, the Senate Majority Leader will introduce a joint resolution increasing the debt limit, which will not be referred to a committee and instead placed directly on the Senate’s calendar. Until January 15, 2022, a non-debatable motion to proceed to the joint resolution may be made, meaning no Senator may prevent consideration of the debt limit increase via a filibuster. If the motion is agreed to, the Senate immediately considers the joint resolution. Senators may not raise points of order against the joint resolution and may not offer amendments. Other motions that would delay passage of the joint resolution are forbidden as well. Debate is limited to 10 hours, so no Senator may filibuster it. After those 10 hours are concluded, the Senate will vote on the joint resolution. The Senate may only consider one joint resolution according to these special procedures and they expire on January 16, 2022.

In one respect, the procedures themselves are not especially remarkable; if they were supposed to govern a non-controversial bill, they could very easily have been put in place through a run-of-the-mill unanimous consent agreement. But the politics of the situation were so contentious that the procedure to establish the procedures was unusual. The procedures were enacted via S. 610, an act that prevents budget cuts to Medicare, among other things. Though the bill was introduced in the Senate, the section providing the special procedures was added in the House, as a self-executing amendment when the House adopted H.Res. 838, the special rule providing for consideration of S. 610. (Of course, even though the language for the rules first came about in a House amendment, the Senate leadership certainly provided the text.) On December 8, S. 610 passed the House by a vote of 222-212. The following day, the Senate invoked cloture by a vote of 64-36, with 14 Republicans voting to end debate. The Senate passed the act itself by a vote of 59-35 on December 9.

When the House of Representatives enacts legislation governing Senate rules, something strange has very likely happened. Often enough, when Congress tries an unusual procedure to bypass a problem, it uses the same procedure when it encounters a similar problem in the future. If there’s another impasse over the debt limit, we could see Congress try to set up a similar procedure again. Or this episode might have wearied Senate leaders of the tendency to dig in on the debt limit, and going forward, the minority party may simply provide sufficient votes to invoke cloture, even though they decline to vote for final passage.

Providing votes for cloture but against passage raises a question: What counts as “support” for a piece of legislation? In this case, Republican Senators oppose raising the debt limit to protest excessive government spending; because it’s good politics; for other reasons; or for some combination thereof. So, their overarching goal for the debt limit negotiations this year has been to have the Democrats lift the debt limit without the minority GOP’s assistance. Since the procedures set up limit debate time and make the motion to proceed nondebatable, the Democrats will not need Republican help on the debt limit joint resolution itself. However, the GOP provided more remote support for the debt limit increase. Since the procedures were appended to a bill the Senate had already passed, it needed to go back to the Senate for another vote. This could be filibustered, so the Republicans needed to deliver 10 votes to invoke cloture. Additionally, the Senate entered into a unanimous consent agreement to speed up the post-cloture time, meaning no Republican objected to it. The Republicans do not need to vote for the debt limit increase itself, but they did provide for it indirectly by facilitating the procedures used to pass it.

It certainly would be easier, and more in line with traditional procedures for the Senate Republicans to have said, that while they oppose the debt limit extension, they thought it only proper that the vote be allowed to take place, and provide the ten votes for cloture. But, this is what McConnell did in October when he was repaid by a rather peevish speech by the Majority Leader claiming the Republicans had tried to “push” the country over a “cliff’s edge” (Congressional Record, October 7, 2021, S6990).

However limited the Republican contributions to this debt limit increase might be, Leader McConnell has gotten some guff from both the Republican base and some Senate colleagues for his strategy. Yet even the reconciliation strategy that the Republicans were floating still required their cooperation to speed up the process. Either way, no responsible elected representative could allow a default on the debt of the United States government, so one way or another the Republicans were going to have to be part of the solution. To say otherwise is disingenuous and irresponsible.

This all serves as a reminder that in the Senate, transacting business without the minority’s buy-in is difficult. The Senate’s rules and procedures provide significant leverage for the minority to block the majority’s agenda and advance its own, and the majority must heed its demands from time to time. By the same token, the minority might, from time to time, be needed—however very remotely—to assist the majority in governing.