It’s practically impossible to miss a Presidential election in the United States. By contrast, the meetings of the Electoral College electors across the country and the official counting of their votes probably pass by most people without much notice. Today, casting and counting Electoral College ballots, following the certification of the votes by each state are not high-profile events, since usually the winner of the election is known well in advance, but the Constitution mandates them. Indeed, from time to time, like this year, it will garner more attention than usual. But it can be very important: if no candidate receives 270 electoral votes for either President or Vice President, the Constitution provides for Congress to make the choice. Thus, the meetings to cast Electoral College votes and the joint session of Congress to count them are still important events. Here we’ll show how the votes are cast and how Congress counts them.

Where We Get the Rules for Counting the Electoral College Votes

Article II, section 1 of the Constitution and the 12th and 20th amendments are the primary sources of law governing the Electoral College and the counting of votes for the Presidency. Title 3, Chapter 1 of the U.S. Code fleshes out the details where the Constitution leaves room for additional regulation.

How, When and Where the Electoral College Votes

According to the Constitution, as amended, each state’s Electors must meet in their own state to vote. This choice was not for the convenience of the electors. Rather, it was a way to protect the integrity of the vote. It is not hard to see how electors might be less easily intimidated inside their own state capitol. In fact, Alexander Hamilton, in Federalist 68, wrote that method of electing the President was constructed to minimize the chance for “tumult and disorder” and the separation of the electors was part of this plan. According to him, the electors’ “divided and detached situation will expose them much less to heats and ferments…than if they were all to be convened at one time, in one place.” Additionally, Hamilton pointed out that the electors themselves could spread “heats and ferments” to the people, and keeping the college divided limited the spread. Finally, dispersing the electors across the country meant it would be harder for malicious actors to corrupt them. In other words, the electors are socially distanced to prevent the spread of diseases to the body politic, rather than the body.

The Congress may determine when the Electors are chosen and the day on which the Electors must vote. Congress has legislated on both these points. According to the U.S. Code, “The electors of President and Vice President shall be appointed, in each State, on the Tuesday next after the first Monday in November, in every fourth year succeeding every election of a President and Vice President.” In other words, it’s the day after the first Monday in November, also known as Election Day. In keeping with the constitutional requirement for the Electoral College, when you go to the polls on Election Day, you’ll notice that, even though the names of the candidates are written prominently, somewhere there’s a reference to the fact that you are voting for the electors who are pledged to vote for the candidates.

Sometimes a candidate or party thinks there is reason to dispute the election of a slate of electors to the Electoral College. The states may legislate procedures to settle such disputes. Federal law provides that if a state has settled a dispute at least six days before the Electoral College meets, the state’s decision is definitive for the purposes of the Electoral College count. This provision of law has been known as the “safe harbor” deadline. The states may still resolve disputes after that date, and Congress may accept the results of disputes settled after it as well. Nonetheless, they would lack the same legal protection as those who met the deadline. The safe harbor deadline in 2020 was Tuesday, December 8.

The Electors meet on the first Monday following the second Wednesday in the December after their election. This means the earliest the Electors could meet is December 13 and the latest would be December 19. In 2020, the Electors will meet on December 14.

According to the U.S. Code, each state legislature may determine where its Electors meet. For instance, in Virginia, where the Congressional Institute is located, the Virginia Code requires that the electors meet at the Virginia Capitol in Richmond at noon on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December. State law requires them to vote for their party’s nominee for the Presidency and Vice Presidency. Virginia’s electors are also entitled to $50 in compensation, along with reimbursement for mileage.

When the Electors meet in their home states, the 12th Amendment to the Constitution requires that they cast two separate ballots, one for President and another for Vice President. The votes are tallied and two lists are drafted. One includes the name of all those who received votes for the Presidency and the number of votes each person received, and the other would contain the same information for the Vice Presidency. The lists are to be signed, certified, sealed and sent to the President of the Senate (the Vice President of the United States) in Washington, DC. According to the U.S. Code, the Electors must make six certificates with the results, sign them, and attach to each of them a list of their names. The Code specifies that each of these should be sent to different people, including the President of the Senate, their state’s secretary of state (not the U.S. Cabinet official), the Archivist of the United States, and the judge of the district in which they meet. The Code specifies that the certificates for the President of the Senate and the U.S. Archivist must be sent via registered mail. Both the secretaries of state and the U.S. Archivist are to receive two sets of lists. If any state’s list fails to reach the Vice President by the fourth Wednesday in December, he is to ask that the state’s secretary of state send a list of votes, and the secretary of state must immediately do so via registered mail. The Vice President is also required to send a messenger to the district judge in receipt of a list of electors, and the judge must deliver it by hand to this messenger. (If this messenger fails to deliver the certificate, the U.S. Code states he is to be fined $1000.)

The Joint Session to Count Electoral College Votes

The Constitution gives a bare outline of how the votes are to be counted once they arrive in Washington, D.C.: The President of the Senate must open the certificates in the presence of both Houses of Congress and the votes are to be counted. The U.S. Code specifies the procedure in much greater detail. Additionally, though the Constitution and U.S. Code provide for the joint session, by tradition, the two Houses agree to a concurrent resolution providing for them to meet. However, the concurrent resolution does little more than recap the procedures that are specified in the Constitution and the U.S. Code.

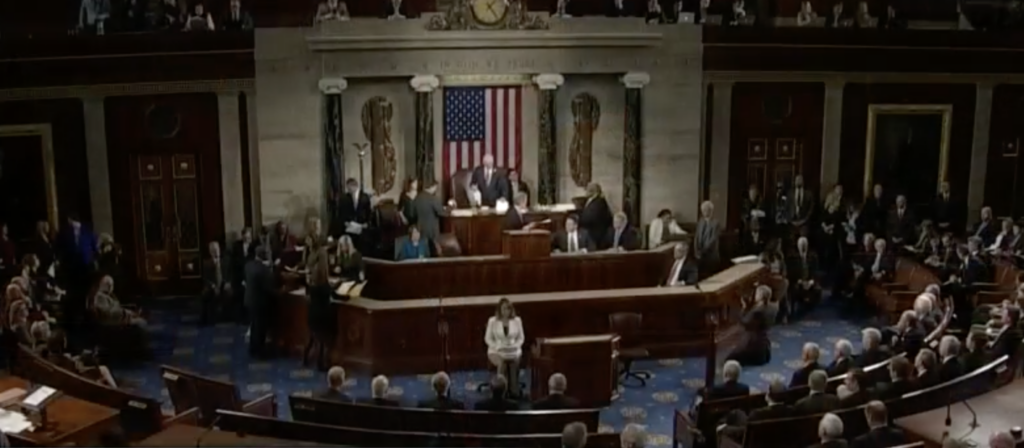

The new Congress is sworn in on January 3, and their first order of business is organizing the Chamber, electing their officers, and, in the House, passing the rules by which they will be governed. The Code states that the Congress must convene in a joint session on at 1:00 pm on January 6 following the meetings of the Electors. The House, with its more spacious Chamber, must host the meeting. This creates a somewhat unusual parliamentary situation: Normally, as the House of Representatives hosts the joint session, the Speaker would preside, but since the Constitution requires the Vice President to count the votes, he does. The Code, in fact, goes so far as to prescribe that the President of the Senate is to be seated upon the Speaker’s chair during the counting of the votes, and that the Speaker is to be seated to his left. It also specifies that Senators are to be seated to his right and Representatives are seated in the remainder of the Hall. The tellers, the Clerk of the House and the Secretary of the Senate are seated at the Clerk’s desk, and the other officers of the two Houses are seated in front of them.

When the time comes for the Joint Session to start, the House has already been gathered in its Chamber. The House Sergeant-at-Arms addresses the Speaker, announcing the arrival of the President of the Senate, the Secretary of the Senate and the Senate. The Senate’s pages precede the party, bearing the electoral vote certificates in wooden chests. They place these on the middle-tier of the rostrum, to the Speaker’s right. Then the Vice President and the Senate file in and take their places. (If you watch a recording, you’ll notice that attendance at this joint session is higher than for a typical House or Senate debate, but not as high as it normally is for something like the annual State of the Union address.)

Each House appoints two tellers to count the votes. Contemporary practice is that the chairmen and ranking members of the Committee on House Administration and the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration serve as tellers. (These two committees have jurisdiction over Federal elections; hence, the designation of their chairmen and ranking members as tellers.) The President of the Senate opens the certificates of the states in alphabetical order, starting with Alabama. Immediately after he opens a certificate, he hands it, along with any accompanying papers, to the tellers. In recent elections, the tellers have simply noted that the certificates appear valid and read the votes, but previously, they would read the entire certificate. The Senate Rules Committee chairman reads the first certificate, followed by the House Administration chairman who reads the second, followed by their respective ranking members who read the third and fourth. This order continues for the rest of the states.

As they read the certificates, they make a list of the votes. Once this process is done, they give the list of votes and the tally to the President of the Senate, who announces the result. After announcing the result, he states that the results, along with a copy of the tally, will be entered into the Journals of the House and Senate. After that, the joint session ends, and the Senate departs from the House Chamber.

When There’s No Electoral College Majority…

When the U.S. Code speaks of the President of the Senate’s announcement of the vote, it notes that this is a “sufficient declaration…if any” person has been elected. The “if any” is important because 12th Amendment to the Constitution requires that the President and Vice President receive a majority of votes from “the whole number of Electors appointed”—i.e., a plurality of the votes is insufficient. In that case, the Constitution provides for what is known as the “contingent election” of the President or Vice President. If no one receives a majority for President, the top three Electoral College (not popular vote) vote-getters enter into a runoff in which the 12th Amendment says the House of Representatives “shall choose immediately, by ballot.” However, one catch is that the 435 U.S. Representatives do not each cast a vote. Instead, they must convene in their state delegations, and each delegation has one vote. Additionally, if no person receives a majority for the Vice Presidency, the Senate chooses from the top two. Unlike the Representatives, each Senator votes individually – meaning North Dakota has the same say as California.

Prior to the ratification of the 12th Amendment, the Constitution failed to require a distinct ballot for the President and Vice President, and each elector voted for two people. The person who received the most votes (provided they received a majority of the electors appointed) would become President, and the runner up would become the Vice President. If none received a majority of the electors appointed, the House would vote from among the top five. If two received a majority of the electors appointed but were tied, the House would select from the top two.

Before the creation of the political parties and the idea of the presidential-vice presidential ticket, that was all well and good. However, by the time of the 1800 election, political parties had been founded and began running tickets. The Federalists ran the incumbent President John Adams along with Charles Cotesworth Pinckney for Vice President. The Democratic-Republicans ran Vice President Thomas Jefferson along with Aaron Burr for Vice President. The Democratic-Republican ticket defeated the Federalists. Keep in mind, that this was the first election under the new Constitution where power was to be handed over from one party to another – something we take for granted today, but where a peaceful transfer of power following an election was unprecedented in most of the world. One of the Democratic-Republican electors was supposed to abstain from voting for Burr, which would have given Jefferson the most votes and the Presidency, while Aaron Burr would finish second and be elected Vice-President. However, something went wrong and Jefferson and Burr tied, meaning the House had to select between the two. In February 1801, the Federalist-controlled lame-duck House met to select the President. While Jefferson had been on the top of the ticket, many Federalists hated the thought of him being President. This resulted in the House being deadlocked for five days and 35 ballots. Federalist Alexander Hamilton, an archfoe of Aaron Burr, intervened, throwing his weight behind Jefferson. “If there be a man in the world I ought to hate, it is Jefferson. But Burr has absolutely no morals, private or public. He listens to nothing but his own ambition,” Hamilton wrote. On the 36th ballot, on February 17, Jefferson finally prevailed, and the country quickly realized it needed to amend the Constitution to prevent such a scenario from happening again.

Since the ratification of the 12th Amendment, the House has decided the Presidency only once, in February 1825, when it elected President John Quincy Adams over Andrew Jackson, who received a plurality of both the Electoral College and popular votes. The Senate has likewise decided the Vice Presidency only once, in 1837. when Richard M. Johnson fell short of the required electoral votes to become Vice President when the entire Virginia delegation of electors refused to vote for him. Johnson was the running mate of Martin Van Buren, who had no problem achieving the necessary votes in the Electoral College. The Senate elected Johnson by a vote of 33 to 16.

The House nearly had to decide one other time following the election of 1876 featuring Rutherford Hayes, the former Republican Governor of Ohio, versus Samuel Tilden, the Governor of New York. Tilden won the popular vote (all of the Southern states had been readmitted to the Union at this point). Tilden won 184 electoral votes, one short of a majority. The two sides disputed the electoral votes of three delegations, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida. These three governments that were still under Reconstruction and occupied by Federal troops charged with protecting the new Black citizens (former slaves) of those states. Tilden was a Northerner, but his political base was the solidly Democratic South.

The Constitution did not provide a way to resolve this fraught issue. To settle it, outgoing President Ulysses Grant appointed a bipartisan commission of five Representatives, five Senators, and five Supreme Court Justices to try to resolve the matter. The selection had seven Republicans and seven Democrats and the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, David Davis. In an effort to sway Davis, Illinois’ Democrat-controlled state legislature appointed Davis to the Senate (remember, this was in the days before Senators were directly elected). Davis accepted the election to the Senate and then promptly refused to serve on the Commission. He was replaced by one of the other Supreme Court Justices, all of whom were Republicans. The Commission then voted in February of the next year to award Hayes all of the outstanding electoral votes by a margin of 8-7, which would have given Hayes the election 185-184.

The Democrats were outraged by the Commission’s decision and tried to filibuster the adoption of the report in the Senate. In the negotiations that ensued, the Democrats insisted on the removal of all remaining Federal troops in the South and that the Republican-controlled Reconstruction governments in the remaining rebellious states be removed and Democrats once again allowed to elect their own governors. The Republicans acquiesced and the filibuster ended, allowing for the election of Hayes. The result of giving into the Democrats’ demand was to leave new Black citizens at the mercy of new governments that would systematically eliminate their rights and enact Jim Crow laws.

And we thought 2020 was a mess.

The U.S. Code does not provide specific procedural vehicles in the case of the presidential election going to the House or the vice presidential election to the Senate. Due to the infrequency of such elections, it is likely that the House would adopt a special rule to lay out the procedures for their election of the President and the Senate would probably adopt a unanimous consent agreement. Each House may, however, look to the examples of the election of John Quincy Adams and Richard M. Johnson for guidance in determining their procedures, and hopefully ignore the election of 1876.

Objecting to Electoral Vote Certificates

If any Member of the House or Senate disputes the validity of the vote certificates sent to Washington, the U.S. Code provides for a procedure to object to votes. When the tellers read each certificate, the Vice President may call for objections. If any Members of Congress find reason to dispute the electoral votes, they must submit their objection in writing, listing the grounds for the objection, and this must be signed by both a Representative and a Senator. After all the objections to a certificate are received, the Senate returns to its Chamber and the two Houses debate the merits of their objections separately. When the Houses separate to judge objections to Electoral votes, each Member of each House may speak for five minutes per objection or question, and they may not speak on the same objection or question more than once. However, debate on an objection (along with any questions that arise in relation to it) is capped at two hours. The Houses may not reject votes that have been lawfully cast but may do so if both Chambers agree they were legally invalid somehow. (In other words, dissatisfaction with the results of the election are not sufficient grounds to reject votes.) Once the Houses dispose of all the objections to a certificate, they reconvene and continue with the counting.

Objections to electoral vote certificates do not happen every election, but they occur from time to time. Since the 2000 election, House Members objected during three joint sessions, in 2001, 2005, and 2017. During the 2017 joint session to count electoral votes, seven House Democrats attempted to raise objections, some of them doing so multiple times. None of them, however, secured the signature of a Senator, meaning Vice President Joe Biden, ruled them out of order. Additionally, when they protested, he ordered them to suspend, since debate is out of order when objections are raised (the proper time for debate is when the two Houses separate to consider the objection). “It is over,” Biden declared in response to one Democrat, drawing roaring laughter and cheers from Republicans.

In the 2001 joint session, a similar scene played out. Fourteen House Democrats rose to object to certificates from the state of Florida—not a surprise, given the heated controversy surrounding that election. This instance was particularly notable since the President of the Senate at the time, Vice President Al Gore, was the defeated candidate for President in the election. As in 2017, no Senator signed the objections offered by House Democrats, so the Gore ruled them out of order. At the end of the joint session, he graciously read out his narrow loss to George W. Bush: 271-266. “May God bless our new President and our new Vice President, and may God bless the United States of America,” he concluded the announcement.

Unlike 2001 and 2017, the 2005 joint session saw an objection that included a signature of both a Representative and Senator, requiring the two Houses to go their separate ways to debate it. Representative Stephanie Tubbs Jones of Ohio and Senator Barbara Boxer of California raised an objection to the votes from Ohio. In the 2001 and 2017 joint sessions, where the Representatives did not have signatures from Senators, they attempted to make statements criticizing the electoral votes. In 2005, neither Representative Tubbs Jones nor Senator Boxer attempted to make such statements during the joint session. Rather, since they had a proper objection, their respective Chambers were able to engage in a full debate once they went their separate ways. Both Chambers rejected the objection by wide bipartisan margins. The Senate disagreed with it by a vote of 74-1, with Senator Boxer as the lone supporter, and the House did as well by a vote of 267-31. After both Houses voted, they reconvened to continue counting the vote. The break in the joint session took about 3 hours and 45 minutes.

Faithless Electors

On occasion, you’ll hear of persons other than the two major party candidates receiving Electoral College votes. Those cast such votes are called “faithless electors” since they fail to vote for the state’s winning candidate. Twenty-four states have laws to either discourage the practice or prevent it outright.

In 2016, former Secretary of State Colin Powell, Senator Bernie Sanders, activist Faith Spotted Eagle, former Representative Ron Paul, and former Governor John Kasich received Electoral College votes for President. Senator Elizabeth Warren, businesswoman Carly Fiorina, Senator Susan Collins, Senator Maria Cantwell and environmentalist Winona LaDuke received votes for Vice President. Three others attempted to cast votes for other candidates, but state laws prevented them: In two states, the electors were replaced with alternates when they attempted to vote for another candidate, and in the third state, the elector given a second ballot to vote for the candidate they pledged to support.

In 2004, one elector voted for Senator John Edwards for both President and Vice President. In 2000, one elector abstained from voting.

(Faithless voting is different from the case of a third-party candidate actually winning a state’s election and Electoral College votes. The last time this happened was in 1968, when Dixiecrat George Wallace won five states in the South. However, Republican Richard Nixon won so handily that these votes did not affect the outcome of the race.)

On July 6 2020, the Supreme Court issued an important decision regarding a faithless elector from Washington state and subsequently one from Colorado. The State of Washington had a law fining an elector who did not vote the way he had promised when nominated to be an elector. In Colorado, the law required that a faithless elector be replaced by an alternate who would follow the results of the popular vote in the state. The Supreme Court upheld the state’s authority in both cases.

Parliamentary Motions During the Joint Session

During a session of the House or Senate, Members typically have the option to make a number of different motions that require the presiding officer to hold a vote. During a joint session for counting the Electoral College votes, there is no debate and the only question that the Vice President may put for a vote is for one of the Houses to withdraw. The joint meeting must last until the result is announced, except for when the two Houses to meet separately to dispose of objections to certificates.

As we said at the beginning, the Electoral College has its supporters and detractors. Among the supporters is Alexander Hamilton, who went so far as to write that the way we elect our President “if it be not perfect, it is at least excellent.” The electoral process has certainly evolved since he lived, but time has shown he was wise: The Electoral College has served our country well. In many, if not most, of our elections since 1788, the electoral college vote was little more than the icing on the cake for the new President. But at other times, it has allowed the nation to resolve close and highly contested elections, by providing the means to deliver a definitive result acceptable to the country. Four times, a President has received fewer popular votes than his opponent yet won the Electoral College. While the proponents of the losing side, were not happy, the Electoral College vote resulted in the peaceful transfer of power from one President to the next.

And when Vice President Pence, acting as the President of the Senate, reads out the results of the electoral ballots of each state and the District of Columbia on January 6, 2021, the United States will have completed its 59th presidential election. That’s a pretty impressive run.