The Senate Byrd Rule, which prevents abuse of the budget reconciliation process, is key in shaping how extensive this year’s tax reform will be.

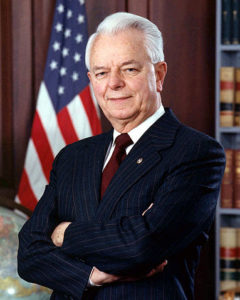

Eagle-eyed observers who have been watching tax reform like a hawk, have been squawking that the tax bill might be a turkey. But even though it was hard to swallow, the Senate ducked a problem with the Byrd Rule without ruffling any feathers. Enough with the bird puns, already, but the Senate consideration of tax reform has been dominated by a rule that applies only to the Senate – the Byrd Rule, named after the late Senator Robert Byrd of West Virginia.

Senator Orrin Hatch, Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, released changes to the Republicans’ tax reform bill on the evening of Tuesday, November 14. One of the most notable modifications was the inclusion of a sunset—an expiration date—for tax breaks for individuals. Republicans want their effort to be a wholesale reform of the tax code, so why did they include an expiration date for some of the core provisions? They are doing that to satisfy the complexities of the Byrd Rule.

The Budget Act of 1974 sets forth the rules that govern how Congress considers a budget blueprint and spending bills. This act requires Congress to draft a budget resolution that contains spending and revenue projections for the upcoming and subsequent fiscal years; these resolutions typically cover 5 or 10 fiscal years. A second feature of the 1974 Budget Act is that it allows for “reconciliation,” which helps Congress achieve its budgetary goals. Reconciliation is an optional process, and Congress may only complete it if the budget resolution contains reconciliation instructions. A reconciliation instruction tells a specific committee that it should report legislation that has some kind of effect on the budget. For instance, the fiscal year 2016 budget resolution contained the instruction: “The Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions of the Senate shall report changes in laws within its jurisdiction to reduce the deficit by not less than $1,000,000,000 for the period of fiscal years 2016 through 2025.” If a budget resolution contains directions for multiple committees within a Chamber, that Chamber’s Budget Committee must stitch the proposals together into a single reconciliation bill. Debate on a reconciliation bill is limited to 20 hours, meaning Senators cannot filibuster it. (For more on the budget process, visit “Budget Basics: Introducing the Federal Budget Process.” For more on the filibuster, visit “The U.S. Senate Filibuster: Options for Reform.”)

Since Senators cannot filibuster a reconciliation bill, it is a powerful way to enact legislation quickly. In fact, it is so effective that Members took note and started loading reconciliation bills with provisions that were irrelevant to the goals of the budget resolution. In 1985, to prevent an abuse of the process, the Senate first adopted what is known as the Byrd Rule, which allows Senators to raise points of order against provisions that are considered “extraneous,” meaning they do not contribute to the goals of reconciliation. When debating the rule, its namesake, Senator Robert Byrd of West Virginia, said, “It was never foreseen that the Budget Reform Act would be used” the way it was. According to him, Senators had so abused reconciliation that “any measure, no matter how controversial” could “be brought to the Senate under an ironclad built-in time agreement that limits debate.” This short-circuited “the deliberative process in this U.S. Senate—which is the outstanding, unique element with respect to the U.S. Senate.” In other words, the Byrd Rule attempts to ensure that the Senate still thoroughly vets important legislation. To enforce the Byrd Rule, Senators may raise a point of order against a provision if they think it fails one of six tests. For instance, the first test is whether the provision “produces a change in outlays or revenues.” The process of vetting a bill to see if it meets the rule’s requirements is called a Byrd Bath – really, we are not making these puns up. If a Senator raises a point of order against a provision of the reconciliation and the Presiding Officer sustains the point of order, the provision is removed from the bill and may not be included again via an amendment. Staff refer to the offending amendment as a “Byrd Dropping.” (However, the point of order can be waived if 60 Senators vote to do so.)

One of the six Byrd tests is whether a provision increases the deficit after the period covered by the budget resolution. If the Chairman of the Senate Budget Committee reports that a provision increases the deficit after the end of the budget window, the Presiding officer may rule that it is extraneous and subject to a point of order. Lowering tax rates naturally affects revenues, so the sunset provisions are one way to ensure that the deficit doesn’t increase after 2027, the last year of the budget resolution. The expiration date for provisions relating to individuals is set for December 31, 2025.

This is by no means the first time Congress wrote sunset provisions into tax legislation. For instance, think of the Bush tax cuts of the early 2000s. In 2001, Congress enacted the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 (EGTRRA), one of the two laws that brought us what are commonly known as “the Bush tax cuts.” This law contained an expiration date of December 31, 2010—i.e., before the end of the period covered by the budget resolution that triggered reconciliation for the tax legislation. The Bush tax cuts’ expiration date made them a political issue. President Obama agreed to extend them for two years in 2010, until Congress passed a law on New Year’s Day 2013 to make most of them permanent. This was part of the “fiscal cliff” episode, a rather unpleasant situation not long after the Great Recession where it appeared that several government policies were set to collide all at once, leading the economy back into a recession. Congress and the President negotiated a deal where most of the Bush tax cuts were made permanent, but it was still neither party’s ideal.

The examples of the fiscal cliff and now the 2017 tax reform show how parliamentary procedure and congressional rules, though they can be complex and difficult to master, substantially affect the public. The policy preferences of the majority party are by no means the only factors that determine the final shape of a piece of legislation—a reality that each Member of Congress eventually collides with. That tough lesson should be reason enough for Members and staff, and even the public, to be conversant with the rules of Congress. Now is a good time to start with the Byrd Rule.

And while learning about the Byrd Rule, it would also be a good time to think about whether reconciliation and the budget process as a whole are the best way to make the country’s budgetary decisions. The Senate Byrd Rule often produces a clash with the House of Representatives, which has no such rule. Since the House does not have filibusters like the Senate, it was never really necessary to use reconciliation to adopt legislation, so there was never the need to place similar Byrd-like restrictions in their procedures. House Members are often frustrated by the Senate’s seeming endless attempts to manipulate the provisions of legislation to meet a budget target ten years away. Since Congress rarely has any idea what will happen with the economy in the next six months, it seems bizarre—bird-brained, if you will—to Members of the House to try to guess what revenues will be in ten years, especially with tax legislation, where even small changes have a dynamic effect on future revenues. Which brings us to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), Congress’ nonpartisan office that reports on the effect of proposed legislation and policy on the economy. The actual dollar amount of various proposals are scored by the CBO, which often uses static models to judge dynamic changes. The model that the CBO relies on is controversial, with Republicans generally supporting dynamic scoring and Democrats generally supporting static scoring. Not to mention the fact that both parties love to start statements beginning “The nonpartisan CBO has found…” and then either praise their own ideas or trash their opponents’ policies, depending on what the latest CBO report says. Surely Congress can find a better way to debate and pass bills related to the budget.

Reforming the budget process is another thing to add to the congressional to-do list, right underneath addressing the expiration of the proposed tax cuts. Regardless of which party is in power in 2025, neither wants to see the average American pay more in 2026. As with the Bush tax cuts and the fiscal cliff deal, Washington will likely come up with some solution in the future.

Small wonder that people think senatorial procedure is for the birds.