Summary: The Gephardt Rule is a House rule that is intended to make it easier to enact adjustments to the debt limit. According to the most recent version of the rule, when the House adopts a concurrent resolution on the budget, the Clerk engrosses a joint resolution suspending the debt limit for the fiscal year and sends it to the Senate. If the Senate passes it without an amendment, the House does not need to vote on it again before it goes to the President for a signature. The Gephardt Rule achieved its purpose in the early years it was in effect, but it has not been especially effective in the last two decades.

Voting to spend public funds is very often a delightful thing indeed. Voting to pay for it never is.

The government has not run a budget surplus in over two decades, so it borrows significant sums to pay for its expenses. The Secretary of the Treasury has broad discretion to borrow to finance government operations, though statutory law imposes a cap on the amount of debt that may be outstanding. The cap is known as the debt limit or the debt ceiling. Once the debt reaches the limit, Congress must either vote to adjust the limit, allow the government to default on its obligations, or find another way to raise sufficient revenues before a default occurs. None of these are appealing options, and Congress typically votes to raise the debt limit, a task that most Members find painful.

To lessen the sting of raising the debt limit, Rule XXVIII of the Standing Rules of the House of Representatives provides one path to reducing the frequency of direct votes on the matter. Sometimes called the Gephardt Rule in honor of Representative Dick Gephardt who introduced its first version, the rule currently provides that when the House agrees to a budget resolution, the Clerk shall prepare a joint resolution suspending the debt limit for the fiscal year covered by the budget resolution. The joint resolution is then sent to the Senate without having the House hold a separate vote enacting it. Instead, the vote on the budget resolution suffices for a vote to adjust the debt limit. The Senate may then take up the joint resolution and consider it. If the Senate amends the joint resolution, it must go back to the House for further action. If the Senate passes the joint resolution without amendment, it then goes directly to the President for approval, without any additional action on the part of the House. Such a situation effectively eliminates a vote for House Members. That is only part of the benefit the rule provides. It also affords Members political cover since those who vote for a budget resolution can say they oppose raising the debt limit and are only voting for the legislation due to the benefits the budget provides. The Gephardt Rule offers both a procedural and political escape hatch for those wishing to avoid a vote to lift the debt limit.

Debates over adjusting the debt limit have raised the prospects of the government defaulting on the Federal debt, so some point to the Gephardt Rule to “solve” the debt ceiling “crisis.” For instance, in 2021, former Federal Reserve Vice Chair Alan Blinder wrote an op/ed for The Wall Street Journal, “A Simple Rule Could End Debt-Limit Shenanigans.” Or a decade ago, The Atlantic published “How Dick Gephardt Fixed the Debt-Ceiling Problem.” So long as the debt limit is with us, the allure of the Gephardt Rule will be too. Without answering the question of whether the House should have the rule, the idea’s popularity makes it advisable to ask whether it is even effective at achieving its purpose: making it more efficient to lift the debt limit.[1] Though it was somewhat effective in the first few years of its 40-year existence, political dynamics have changed in such a way that it has helped in recent years and will not likely be very effective in the future.

Trying to Take the Sting Out of Debt Limit Votes

Representative Dick Gephardt, a Democrat from Missouri who served in the House from 1977 to 2003, originally proposed the rule to expedite lifting the debt limit. Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill of Massachusetts charged Gephardt with whipping Democratic votes to increase the debt limit—a rather unpleasant task. “We [Democrats] were in charge of Congress, but nobody ever wanted to vote for it…Every time it came up I had to go to every member and seek their vote. It was painful and difficult, and, I thought, unnecessary,” he later recalled.[2] After consulting with the Parliamentarian, he devised the first iteration of the rule. It directed the Clerk to engross joint resolutions increasing or decreasing the permanent and temporary debt limits once both Chambers agreed to a single concurrent budget resolution which stated that the government should have a different level of public debt.

The Gephardt Rule was attached to an increase in the debt limit that the House passed in September 1979. While the House considered the measure, Gephardt argued that the debate on the budget resolution, rather than that for a separate piece of stand-alone legislation, was the appropriate place to consider an increase in the debt limit, as it allowed Members to consider the nation’s fiscal priorities as a whole. The debate on the debt limit “legitimately and logically” belonged within “the context of when we vote for the spending that creates the need to change the debt ceiling.”[3] Further, he argued it was a way for the House and its committees to reduce the amount of time spent “doing unnecessary things.”[4] He and other supporters of his rule argued that appropriations legislation already imposed obligations on the government, so raising the debt limit simply allowed the government to pay for its bills (a refrain that comes up virtually whenever there is a dispute over the debt limit).

Opponents of the Gephardt Rule offered mirror-image arguments of its supporters, focusing both on the proper context for debating the resolution and Congress’ ability to manage its work. They said that the prevailing practice of requiring a separate vote to increase the debt limit would both focus attention on the size of the national debt and hold Congress accountable to the public. In one comment, Rep. Del Latta, a Republican from Ohio, summed up both arguments:

I think the American people are not going to look kindly on any action this House might take to put this matter underneath the rug so that it will be passed very quickly, hopefully in the budget resolution, without directing the attention of the American people to that ever-increasing, yes, ever-escalating national debt that is put on them because of the big-spending habits of this Congress.[5]

Additionally, some pointed out that pairing a debt limit increase with the budget resolution could delay the adoption of the budget resolution. Though the contemporary budget process, created through the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974, had been in existence for only a few years, Congress’ capacity to agree to the budget resolution was already an issue of concern. One opponent of the Gephardt Rule noted that the year’s budget resolution was “in limbo” and “timeliness…has not always been present with the budget process.”[6] (Congress is arguably even less timely in its adherence to the budget process today, as it often does not even complete a budget resolution.)

Arguments about the proper place to debate the debt limit increase were all well and good, but Members raised another issue that was perhaps more important: the political and electoral considerations that drove the decisions regarding the debt limit. Supporters of the Gephardt Rule derided opposition to increasing the debt limit as a political show. For instance, Rep. Edgard Lanier Jenkins, a Democrat from Georgia, pointed out that under Democratic Presidents, Republicans opposed increases in the debt limit. Jenkins, however, was honest about his own party’s political tactics. “When we have a Republican President in the White House, then many of the Democrats do not feel obligated to vote for the debt limit legislation,” he said.[7] But political considerations went both ways. Rep. Barber Conable of New York, a Republican who actually supported the Gephardt Rule, noted that the majority party encourage minority Members “to be responsible” and vote for the debt limit increase “so more of them”—the majority Democrats—could vote against it.[8] Depending on the circumstances, increasing the debt limit was either a political liability or boon to either party.

At the time, the politics of separate votes to increase the debt limit increase generally favored the minority Republicans, and Republican Rep. John Rousselot of California offered an amendment to strip the Gephardt Rule from the bill. It failed by a vote of 132-283. Most of the Republicans (112), voted for the amendment, though a strong minority of (40), including the Republican Leader John Rhodes of Arizona and Whip Bob Michel of Illinois, voted against it. Twenty Democrats voted for the amendment. The underlying bill itself, which included the increase in the debt limit, passed by a vote of 219-198, with 52 Democrats voting against it.[9] The greater number of Democrats voting against final passage of the debt limit increase than for the amendment to strip the Gephardt Rule from the bill suggests just how appealing it was to avoid voting for a debt limit increase. In other words, a considerable number of Democrats likely wanted to make it easier to raise the debt ceiling, while still going on record against raising the debt limit at that moment.

How Has the Gephardt Rule Fared Over Time?

For the first decade and a half of the Gephardt Rule’s existence, the Democrats controlled the House. In that period (1980 through 1995), the Gephardt Rule generated 15 joint resolutions to increase the debt limit. The Senate passed seven of these without amendment—a respectable amount, though still less than half. It amended five (requiring another House vote), laid aside one, and did not take any action on two.

In January 1995, Republicans took control of the House for the first time in 40 years. They left the Gephardt Rule in place. However, five months into the 104th Congress, the House voted to suspend it with respect to the budget resolution they were debating for fiscal year 1996. The majority did so as a matter of public accountability. “There’s no free ride,” said Rep. Gerald Solomon of New York, the Chairman of the Rules Committee. “We are going to have to put our name on the line.”[10] Another Republican called the suspension a “courageous step” to require a separate vote on the debt limit that year, urging the same for the future too.[11] The resolution suspending the Gephardt Rule, which was also the special rule for the budget resolution that year, was agreed to by a vote of 255 to 168, with 27 Democrats joining the Republicans to support it. The following year, with the Gephardt Rule suspended, the House did vote on the debt limit—multiple times actually, as Congress enacted two temporary measures to get through a standoff with President Bill Clinton before finally enacting a permanent increase in March 1996. Each of the final votes on these debt limit laws had strong bipartisan majorities.[12] Additionally, the Federal Government ran budget surpluses for the fiscal years 1998 through 2001, making it unnecessary to raise the debt ceiling. Nonetheless, the House voted to suspend the Gephardt Rule for these years.

At the beginning of the 107th Congress, on January 3, 2001, the House, controlled by Republicans, repealed the Gephardt Rule. The Chairman of the Rules Committee, Rep. David Dreier of California, said that requiring a separate vote on the debt limit would “restore accountability” to the public.[13] Nothing else, however, was said about the matter, which is not entirely surprising, since debates on the rules package typically cover numerous issues. During this Congress, the House and Senate enacted one debt limit increase, without the benefit of the Gephardt Rule.

At the beginning of the 108th Congress (2003-2005), the House, still controlled by Republicans, reinstated the Gephardt Rule. Unlike when the House first instituted the rule in 1979, the Democrats in 2003 were all for holding separate votes on increasing the statutory debt limit. They argued that the separate vote on the debt limit held Republicans accountable to the public and promoted fiscal responsibility. For instance, Rep. Gene Taylor of Mississippi argued, “One of the few things that controlled their urge to run up the bill and stick our kids with it was at least a law that said we had to vote to raise the debt limit.”[14] Another said, “They should be willing to stand up and be counted when the time comes to pay the bill by raising the debt limit.”[15] To rebut the charge that the Republicans were trying to evade responsibility to the public, Dreier said, “Every Member will be accountable because that vote [on the debt limit] will be cast when we deal with the budget resolution itself.”[16] Dreier’s statement is true in a certain sense, though rather in tension with what he had said two years before, when he spoke in favor of repealing the Gephardt Rule—not unlike the tension between the minority Democratic statements in 2003 and in 1979 when they were in the majority ushering in the Gephardt Rule. The parties’ exchange of positions on the Gephardt Rule exemplified a phenomenon in legislatures where a party favors a particular rule when in the majority and then opposes it while in the minority.

From January 2003 through January 2007, when Republicans controlled the House and had the Gephardt Rule in place, it resulted in two joint resolutions, both of which passed the Senate without amendment. For two of those four years, Congress did not complete action on a budget resolution, precluding the operation of the Gephardt Rule. The Republicans lost the House in the midterm elections of 2006, and when the Democrats took control in January 2007, they left the Gephardt Rule in place for the 110th and 111th Congresses. During this four-year majority, the Gephardt Rule resulted in three joint resolutions, one of which passed the Senate without amendment; one which passed with amendment, thereby requiring an additional House vote; and one that did not pass the Senate at all. The two Chambers did not agree to a budget resolution for fiscal year 2011, so the Gephardt Rule did not produce a joint resolution. The Democrats then lost the House in the 2010 elections.

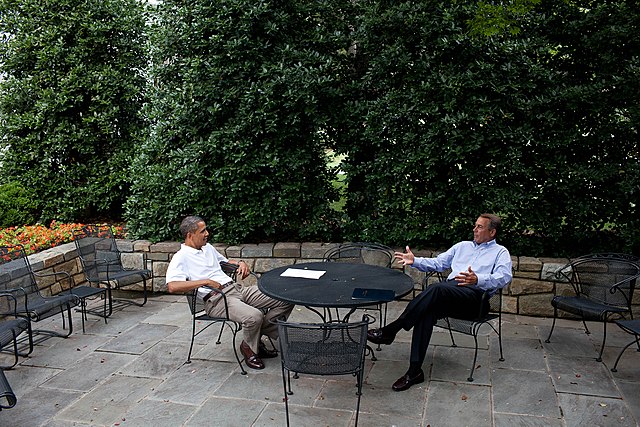

When the Republicans took control in January 2011, they struck the Gephardt Rule once again, with little fanfare during the debate on the rules package for the 112th Congress. The new Republican House majority came to office energized to combat what it saw as fiscal irresponsibility. “Without significant spending cuts and reforms to reduce our debt, there will be no debt limit increase,” declared Speaker John Boehner in May 2011 at the Economic Club of New York.[17] The debt limit was one way of exerting leverage over the government’s finances. In addition to being a symbol of a change in the House’s approach to the debt limit, eliminating the Gephardt Rule also forestalled any possibility that the Senate could pass a Gephardt Rule-generated joint resolution. Eventually, the debate between the Obama Administration and the Congress led to the passage of the Budget Control Act of 2011, which provided for increases to the debt limit. It also created the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction (known colloquially as the Super Committee) which was to recommend ways to cut the deficit by at least $1.5 trillion over the next decade; the failure of this committee to make recommendations led to automatic budget sequesters. It also imposed caps on discretionary spending for the next decade. The Budget Control Act of 2011 set the stage for budget negotiations for the rest of the decade.

Unlike the previous Republican majority which did an about-face on the Gephardt Rule, it was never reinstated during the House Republican majority that lasted from January 2011 until January 2019. The decision not to reintroduce the Gephardt Rule at all during this period might strike some as somewhat surprising, as two political shifts increased the likelihood that it would have eased the burden of lifting the debt limit. First, in 2015, the Republicans took control of the Senate. Additionally, two years later, with the election of Donald Trump to the presidency, the Republicans had a two-year period of unified government—a situation in which the Gephardt Rule should have been maximally effective. During the 2011-2019 House Republican majority, Congress enacted seven laws adjusting the debt limit, two of which were passed in the during the period of unified government.[18]

When the Democrats regained control of the House at the beginning of January 2019, they reinstated a modified version of the Gephardt Rule. This iteration had two critical changes. First, it made the engrossment of a joint resolution dependent on the adoption of a concurrent budget resolution by the House alone, not of the bicameral agreement on a budget. (While it is not known why, specifically, this change was made, it is perhaps a reflection of the fact that the House and Senate so often fail to agree to a budget resolution.) Second, the new rule generates a joint resolution suspending the debt limit rather than one raising or lowering it to a specific dollar amount as it previously had done. (This reflects the new practice of suspending the debt limit, rather than lifting it.) Majority Leader Steny Hoyer of Maryland called the rule a “common-sense” practice.[19] By contrast, Republicans accused Democrats of fiscal irresponsibility. Rules Committee ranking member Tom Cole of Oklahoma said the rule allowed Democrats “to spend with impunity, without worrying about hitting the limit on the national credit card.”[20] Another Rules Committee Republican, Rep. Michael Burgess of Texas, said removing the requirement that the Senate concur with the budget before the joint resolution is engrossed was “a dangerous policy.”[21] Whether or not reinstating the modified Gephardt Rule was “dangerous,” it has been of no practical effect since 2019. Since then, the House has voted on three concurrent resolutions on the budget, and the House suspended the Gephardt Rule for each of them.[22] Thus even the supporters of the Gephardt Rule hesitate to use it.

This sketch of the history of the Gephardt Rule suggests that it is of mixed success in alleviating the burden of lifting the debt limit. It was in place from 1980 through 2010, and in 11 of those years it was suspended or repealed entirely. In the first five years, it had a successful track record, leading to seven joint resolutions that passed the Senate without amendment. But after that, its effectiveness dropped off considerably. For the rest of the time that it was in effect, it produced only three additional joint resolutions that the Senate adopted without amendment. But during the period 1980 through 2010, Congress enacted 47 debt limit increases in total, so the 10 Gephardt Rule joint resolutions that passed the Senate without amendment accounted for just over 21 percent of the increases in 30 years. The Gephardt Rule generated an additional ten joint resolutions, six of which the Senate amended, thereby forcing the House to vote again before they became law. (The Senate also did not pass four joint resolutions that the Gephardt Rule generated.) By contrast, from 1980 through 2010, Congress enacted 31 debt limit increases via legislation that was not produced by the Gephardt Rule. Again, from January 2011 through January 2019, the House did not have the Gephardt Rule, and Congress enacted seven debt limit adjustments. And under the reformed Gephardt Rule that was instituted in 2019, it has not even generated a single joint resolution as the House has suspended it for each budget resolution.

The Limitations of the Gephardt Rule

The Gephardt Rule achieves its intended purpose: 1.) when debt-limit politics, especially in the House, favor the rule, and 2.) when the House and Senate already agree on the appropriate level of the debt limit. The Gephardt Rule worked well in the first five years in which it was in effect, when Congress enacted seven of the ten Gephardt-generated joint resolutions without amendment by the Senate. From 1985 through 2002, however, it was not especially effective. This is due partly to the Senate amending joint resolutions that the Gephardt Rule generated, meaning the House had to take another vote. Other times, it was due to the House Republicans’ desire to accept the responsibility of separate votes on the debt limit and/or to use the votes to extract concessions from a Democratic President. Further, even in the period of a restored, modified Gephardt Rule from January 2019 through the present, the House Democrats have suspended its operation, suggesting that it is not politically advantageous or feasible in the current situation. Today’s version of the Gephardt Rule makes adjusting the debt limit almost as efficient as possible, and yet it has not made lifting the debt limit easier.

Going forward, it is likely that the Gephardt Rule will continue to be an ineffective method of “solving” the debt limit “problem.” First and foremost, divided government will, more often than not, be the norm for the time being. In such cases, it is unlikely that the Senate will simply take up the House’s Gephardt Rule-generated joint resolution, and Congress will need to come to some kind of alternative agreement to adjust the debt limit. Additionally, even when there is a unified government, as there was from January 2017 through January 2019 (under Republicans) and from January 2021 through the present (under Democrats), the politics of the debt limit have still favored an alternative arrangement. One simple reason for this is that the Gephardt Rule covers only one fiscal year, whereas it is generally more advantageous for debt limit adjustments to cover more extended periods, so Congress does not need to revisit the issue so frequently. Similarly, over the last several years, adjustments to the debt limit have been part of larger budget negotiations, meaning the Senate would not take up a Gephardt Rule joint resolution. Finally, since the House often enough does not agree to a budget resolution, it is not even possible for the Senate to take up a joint resolution in such years. Even very clever congressional rules cannot make it easier to enact legislation when politics does not favor it.

The failure of the Gephardt Rule to meaningfully alleviate the political burdens of adjusting the debt limit today is in keeping with the general disarray of the budget process. When the House first adopted the Gephardt Rule, it was activated when both Chambers agreed to a single budget—which actually happened in those days, even when each party controlled one of the Chambers. We can now no longer assume that Congress will produce a budget even when one party controls both Chambers. More tellingly, government shutdowns due to the failure to enact spending bills, while not the norm, often pose credible threats to the country. Such symptoms of budgetary disarray point to the deep-seated policy and partisan disagreements between Republicans and Democrats. Procedural workarounds such as the Gephardt Rule can do little in the face of fundamental divisions among Members and contradictory incentives for the parties. For better or worse, the prospect of failure to raise the debt limit is a powerful incentive to reach budget compromises in a highly partisan Congress. The Gephardt Rule may be a more efficient way to raise the debt ceiling from a legislator’s perspective, but until the parties can come to a greater agreement on limiting the reasons for raising the debt ceiling, it is more likely to be considered a political fig leaf than a good procedure.

[1] Assessing whether the House should adopt the Gephardt Rule involves both questions of whether it is effective and whether it is in the public interest. If it is not effective, why bother? If it is, there are still questions of whether it is advisable. For instance, opponents of the rule say it obscures public accountability. One could acknowledge that the rule is effective while still opposing it on other grounds.

[2] Joshua Green, “How Dick Gephardt Fixed the Debt-Ceiling Problem,” The Atlantic, May 9, 2011. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2011/05/how-dick-gephardt-fixed-the-debt-ceiling-problem/238571/. Accessed August 30, 2021.

[3] Rep. Richard Gephardt speaking on H.R. 5369, on September 26, 1974, 96th Congress, 1st session, Congressional Record 125, 20:26342. Available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1979-pt20/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1979-pt20-4-2.pdf.

Properly speaking, the concurrent budget resolution did not authorize spending, appropriate funds, or set tax policy, so it was a stretch to say the concurrent budget resolution “creates the need to change the debt ceiling.”

[4] Rep. Richard Gephardt speaking on H.R. 5369, on September 26, 1974, 96th Congress, 1st session, Congressional Record 125, 20:26342. Available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1979-pt20/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1979-pt20-4-2.pdf.

[5] Rep. Del Latta speaking on H.R. 5369, on September 26, 1974, 96th Congress, 1st session, Congressional Record 125, 20:26345. Available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1979-pt20/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1979-pt20-4-2.pdf.

[6] Rep. John Rousselot speaking on H.R. 5369, on September 26, 1974, 96th Congress, 1st session, Congressional Record 125, 20:26346. Available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1979-pt20/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1979-pt20-4-2.pdf.

[7] Rep. Edgar Lanier Jenkins speaking on H.R. 5369, on September 26, 1974, 96th Congress, 1st session, Congressional Record 125, 20:26342. Available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1979-pt20/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1979-pt20-4-2.pdf.

[8] Rep. Edgar Lanier Jenkins speaking on H.R. 5369, on September 26, 1974, 96th Congress, 1st session, Congressional Record 125, 20:26343. Available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1979-pt20/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1979-pt20-4-2.pdf.

[9] “CQ House Votes 462-465,” in CQ Almanac 1979, 35th ed., H-134. Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly, 1980. http://library.cqpress.com.databases.library.georgetown.edu/cqalmanac/file.php?path=Floor%20Votes%20Tables/1979_House_Floor_Votes_462-465.pdf#xml=http://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/pdfhits.php

[10] Rep. Gerald Solomon speaking on H. Res. 149, on May 17, 1995, 104th Congress, 1st session, Congressional Record 141, 82:H5108. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/104/crec/1995/05/17/CREC-1995-05-17-house.pdf.

[11] Rep. Cliff Stearns speaking on H. Res. 149, on May 17, 1995, 104th Congress, 1st session, Congressional Record 141, 82:H5115. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/104/crec/1995/05/17/CREC-1995-05-17-house.pdf.

[12] U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, Votes on Measures to Adjust the Statutory Debt Limit, 1978 to Present, by Justin Murray, R4184 (2012), 4.

[13] Rep. David Dreier speaking on H. Res. 5, on January 3, 2001, 107th Congress, 1st session, Congressional Record 147, 1:H9. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/107/crec/2001/01/03/CREC-2001-01-03-house.pdf.

[14] Rep. Gene Taylor speaking on H. Res. 5, on January 7, 2003, 108th Congress, 1st session, Congressional Record, 149, 1:H16-17. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/108/crec/2003/01/07/CREC-2003-01-07-house.pdf.

[15] Rep. Dennis Moore speaking on H. Res. 5 on January 7, 2003, 108th Congress, 1st session, Congressional Record, 149, 1:H16. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/108/crec/2003/01/07/CREC-2003-01-07-house.pdf.

[16] Rep. David Dreier speaking on H. Res. 5, on January 3, 2001, 107th Congress, 1st session, Congressional Record 147, 1:H17. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/107/crec/2001/01/03/CREC-2001-01-03-house.pdf.

[17] Speech of Speaker John Boehner at The Economic Club of New York. May 9, 2011. The Economic Club of New York. Transcript available at https://www.econclubny.org/legacyarchive/-/blogs/john-boehner. Accessed December 12, 2022.

[18] U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, The Debt Limit Since 2011, by D. Andrew Austin, R43389 (2021), 7.

[19] Rep. Steny Hoyer speaking on H. Res. 6, January 3, 2019, 116th Congress, 1st session, Congressional Record 165, 1:H24. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/116/crec/2019/01/03/CREC-2019-01-03-house.pdf.

[20] Rep. Tom Cole speaking on H. Res. 6, January 3, 2019, 116th Congress, 1st session, Congressional Record 165, 1:H11. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/116/crec/2019/01/03/CREC-2019-01-03-house.pdf.

[21] Rep. Michael Burgess speaking on H. Res. 6, January 3, 2019, 116th Congress, 1st session, Congressional Record 165, 1:H30. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/116/crec/2019/01/03/CREC-2019-01-03-house.pdf.

[22] See H. Res. 85 and H. Res. 601, both from the 117th Congress. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-resolution/85/text; https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-resolution/601/text.

For fiscal year 2021, the House agreed to both a House concurrent resolution and a Senate concurrent resolution on the budget. The House provided for consideration of the House concurrent resolution via a special rule that suspended the Gephardt Rule for any budget resolution for fiscal year 2021. The House later adopted the Senate budget resolution via H. Res. 101. H. Res. 85, the special rule for the House concurrent resolution, was written in such a way that it was not necessary for H. Res. 101 to suspend the Gephardt Rule as well.