Often enough, Members of the House and Senate will be elected to another office or be offered an appealing position in the Executive Branch or private sector during their term. Unfortunately, others pass away or, due to ethical misconduct, must resign in disgrace or even more rarely, are expelled by their Chamber. Thus, during each Congress, several vacancies will occur, usually in the House and sometimes in the Senate, and the way they are filled is constitutionally significant and can impact policy.

Understanding how such vacancies are filled is important since people determine policy, even though turnout for special elections is lower than those for regular elections. Those who succeed the former Member are often enough elected for subsequent terms. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi of California, for instance, was first elected to Congress in June 1987 to replace her dear friend the late Representative Sala Burton. (Incidentally, Sala Burton was elected to fill the vacancy caused by the death of her husband, the liberal legend Phil Burton. That’s an example of “widow’s succession,” where the wife of the deceased is appointed or elected to her husband’s seat.) Of course, Pelosi’s rise to the Speakership took decades. Some vacancies have more immediate consequences. For instance, when Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy died in August 2009, the governor appointed a Democrat to replace him. However, in the subsequent special election, the people elected Senator Scott Brown, a Republican who pledged to vote against healthcare legislation known as Obamacare, meaning the GOP could sustain a filibuster. Brown’s election also illustrates another point: Special elections are often referendums on the current administration or the congressional majority. Perhaps Brown’s election in a normal year would have ended the effort to enact Obamacare, but that leads us back to our first example of why vacancies can be important: Nancy Pelosi was Speaker and she managed a successful strategy to see the effort through to completion. It’s not just that elections have consequences, special elections can have very special consequences.

As the examples of Nancy Pelosi and Scott Brown suggest, House and Senate vacancies are filled differently, which reflects the principles and provisions of the U.S. Constitution that directs the process for filling vacancies in House and Senate seats that occur during the middle of a Congress.

For a vacancy in the House, Article I, section 2, provides that the chief executive of each state is to call for an election to fill the vacancy. For the Senate, the Seventeenth Amendment, which provided for the popular election of Senators, specifies that the executive should call for an election, and it also allows the state’s legislature to authorize the governor to make a temporary appointment until the special election is held. The differences in methods of filling in vacancies reflect the country’s principles of both checks-and-balances and federalism.

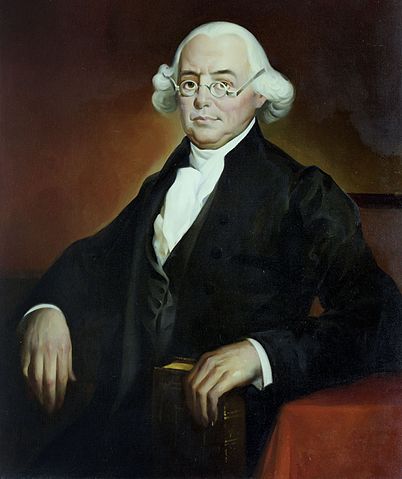

The differences in how House and Senate vacancies are filled can be traced to the Framers’ debates over how to create Congress. Having two chambers in Congress is part of the Federal Government’s checks-and-balances: Each chamber may stop the other’s legislation. In Federalist 51, James Madison noted that “different modes of election” is one way to “remedy” the likelihood of legislative tyranny. Hence, the House was to be elected by the people and the Senate by state legislatures. Additionally, having the state legislatures elect Senators greatly reinforced the idea that the Senate was to represent states, their sovereignty, and their governments.

Originally, since the Constitution entrusted the election of Senators to the state legislatures, so it was with vacancies. Additionally, it authorized the governor of a state to appoint a Senator when a vacancy arose only if the legislature was in recess. The delegates at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 debated the method of filling vacancies on August 9. James Wilson of Pennsylvania opposed allowing state executives to make temporary vacancies since he thought that it removed the choice too far from the people (in many states, the governor was then selected by the legislature); besides, the legislatures, he thought, would meet often enough that it would not be impractical for the legislature to retain the power to appoint any Senate vacancy. Other delegates thought that it was necessary since some state legislatures met only once a year, so some vacancies could extend for lengthy periods. Additionally, the executives were only authorized to make temporary appointments, not mandated to, and when the meeting of the legislature was near, they would refrain from using that power. Most of the delegations voted to keep the provision allowing the state executives to make temporary appointments; Maryland was divided on the question, and Pennsylvania opposed it. So, it remained in the final version of the Constitution that was sent to the states for ratification.

The delegates at the Convention did not have a similar debate over the manner of filling vacancies to the House: There was no question that the people would elect their representatives rather than have the executive make a temporary appointment. At the beginning of the Convention, there had been some debate about the way the Representatives would be elected, but once that was settled, it appears there was no subsequent debate about how vacancies would be filled, so no suggestion of providing the state executives the power to do so. Unlike the provisions for electing Senators, this part of the Constitution has not been amended.

In 1911 and 1912, Congress debated a joint resolution that became the 17th Amendment to the Constitution, which provided for the direct election of U.S. Senators. When the Senate debated the House’s joint resolution in May 1911, Senator Joseph Bristow of Kansas offered an amendment in the nature of a substitute which the Senate adopted. During the debate, he said he based the language for filling up a Senate vacancy on the language that the Constitution used to fill up a House vacancy. He said he also modeled the language allowing the legislatures to authorize the governors to make temporary appointments on the Constitution’s provision empowering the executive to do so. (So far as he made some provision for the executives to make temporary appointments, he did model it on the Constitution. However, the Constitution’s original text directly authorizes the state executives to make temporary appointments; Bristow’s amendment makes that authority depend on the state legislature’s say-so. In other words, Bristow’s amendment could have been closer to the original wording of the Constitution than it actually was.) On June 12,the Senate was evenly divided on Bristow’s amendment, and the Vice President voted in the affirmative. Immediately after voting on Bristow’s amendment, the Senate passed the joint resolution. Almost another year passed before the two Chambers agreed to the final version that was sent to the states for ratification. After enough states ratified the amendment, it officially became part of the Constitution on May 31, 1913.

States have exercised their constitutional discretion in filling senatorial vacancies in different ways. Some states have relatively simple provisions for appointing and electing Senators. An example of a relatively simple state provision is Florida’s law, which permits the Governor to make a temporary appointment and requires him to call for an election to be held at the next general election. Likewise, Virginia requires the Governor to hold an election at the next general election, or if the vacancy opens within 120 days of the general election, the vacancy will be filled at the subsequent general election. It also allows him to make a temporary appointment, which shall last until a successor is elected.

Other states have lengthier provisions governing how Senate vacancies shall be filled. For instance, Nebraska law requires the governor to fill the office with “a suitable person.” It also includes a three-pronged timeline specifying how such a “suitable person” will hold office. If the vacancy opens up 60 days or less before a general election and the term of office for the vacant seat is over at the end of the Congress, the appointee serves out the duration of the term. If the term for the vacancy extends beyond the end of the current Congress, and the vacancy occurs within 60 days of a general election, the temporary appointee serves until January 3 which follows not the upcoming general election but the one after that. (In other words, in that case, the temporary appointee will be in office not just for one general election but two.) Finally, if a vacancy occurs more than 60 days before a general election, the appointee serves until the January 3 following the election. So, if a vacancy happens more than 60 days before the election, and the term expires on the next January 3, the temporary Senator finishes the term; if the term does not expire on that January 3, the person who is elected in the general election finishes the term.

Another example of a more elaborate provision is, California law, which provides a timeline for special elections, but notes that if such elections were to fall after the expiration of the vacant term, the Governor should consult with the California Secretary of State to see whether it’s feasible to hold an election; the Governor then may choose whether to hold an election.

Wyoming has elaborate procedures directing the Governor’s choice of a temporary appointment. When a Senate vacancy occurs, the Governor must immediately notify the state party committee of the party that the departing Senator belonged to. Within 15 days, the state party committee must meet to recommend three people to the Governor. Within five days of receiving these nominations, the Governor must select one. It also provides for alternative procedures if the departing Senator had not been a member of a party when he or she was elected, but according to the Senate, Wyoming has never elected a Senator who was not a member of one of the major political parties—so its provisions give the parties significant leverage in dictating temporary appointments.

Though most states allow for the governor to make a temporary appointment, according to the Congressional Research Service as of 2021, five (North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin) fill Senate vacancies exclusively through elections.

In addition to the Constitution, Federal statutory law provides additional regulations for filling vacancies in the House. Title II, chapter 1, section 8 of the U.S. Code authorizes each state’s or territory’s legislature to regulate the time for holding special elections in general. The exception to this general provision is for so-called “extraordinary circumstances,” which occurs when the Speaker announces that there are more than 100 vacancies in the House. During such an extraordinary circumstance, a special election must be held within 49 of the Speaker’s announcement. (This requirement for a special election within 49 days of the announcement is lifted if there will be a normally scheduled general election within 75 days of the announcement or a special election was scheduled prior to the announcement anyways.) The provisions of law providing for “extraordinary circumstances” was included as a title of the Legislative Branch Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 2006 and was a result of deliberations about how to ensure the continuity of government following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

The provision for “extraordinary circumstances,” thankfully, has never been necessary. A handful do, however, occur each Congress, and the way House and Senate vacancies are filled reflects the country’s constitutional design and the public’s preferences. And, moreover, the new Member of Congress may well make an indelible mark on the institution, so watch out whenever a vacancy occurs.