Summary: President Joe Biden’s plan to forgive student loans exceeds his authority under the Constitution and Federal law—an encroachment on Congress’s authority. To reaffirm congressional authority, the House should employ the Boehner Doctrine and vote to sue the Biden Administration. Though most House Democrats may support the President, moderate Democrats may join the minority Republicans by voting for a resolution to authorize a lawsuit.

It is fairly easy to come up with policy reasons why President Biden’s plan to forgive $400 billion worth of college debt is bad. The dollar amount of this loan forgiveness will likely exceed the entire amount of the much-ballyhooed, if wrongly named, Inflation Reduction Act. A loan is a legal contract that people willingly enter. What other loans are people just allowed to walk away from without declaring bankruptcy? It is deeply wrong to make people who could not go to college pay for people who do. From an equity perspective, it is helping the well-to-do at the expense of hard-working men and women. It is another $400 billion infusion into the economy that will just make inflation worse – and it will also make it last longer. But perhaps most importantly, forgiving this debt requires a law passed by Congress, not an unconstitutional presidential executive action.

Standing and the Student Loans

The problem with challenging the Biden Administration in this is, how to stop it? Plaintiffs in a lawsuit must demonstrate that they have standing to sue, which means that the defendant’s actions must have injured them, and the courts can right the alleged wrong.

Who then, according to the courts, has the legal standing to file suit against the Biden Administration?

Normally, a private citizen or organization would sue the government, asking Judicial Branch to halt some action on the part of the Executive Branch. Could a private citizen who is not eligible for the loan repayment argue that they were injured on the grounds that the plan transfers a massive debt from one group of citizens to the population as a whole? A court would likely rule that the injury is too diffuse to qualify for standing.

However, the economic impact of the Administration’s plan is not the only issue at stake here. Congress’s power to control to set policy and control the Federal purse strings specifically is also at stake. Thus, the House of Representatives as a body has the standing to sue and can assert itself by voting to authorize a lawsuit on its behalf.

The Boehner Doctrine: Precedent for Institutional Lawsuits

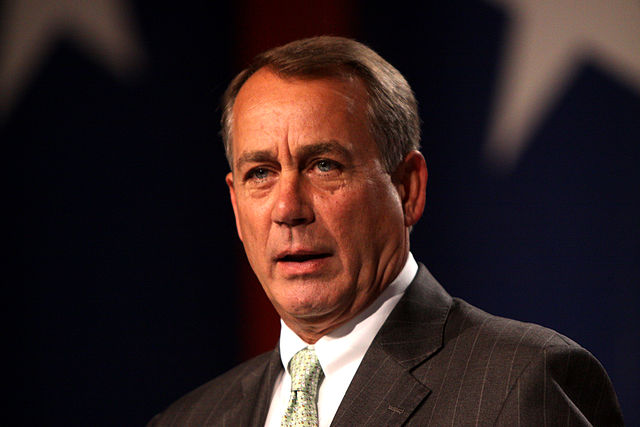

According to the “Boehner Doctrine,” the House may vote to authorize a lawsuit alleging that the Executive has trespassed upon the institution’s constitutional powers and privileges. By voting, the House takes the position that it is acting as an institution and not merely as a group of Members.

The Boehner Doctrine, as we call it, comes to us from the Speakership of John Boehner of Ohio, who presided over the House from January 2011 through October 2015. Throughout Boehner’s Speakership, the government was divided between the Republicans and Democrats, making legislative solutions to vexing policy issues difficult. President Barack Obama pledged to use Executive power to advance his agenda. Republicans objected that many of his actions were abuses of authority. One example Republicans cited was the Administration’s use of funds for one program to prop up Obamacare, an action they said was unconstitutional since it required an appropriation.

“I believe the House must act as an institution to defend the constitutional principles at stake and to protect our system of government and our economy from continued executive abuse,” he said in July 2014. At the end of the month, the House agreed to H.Res. 676, which authorized the Speaker to sue to uphold the House’s constitutional prerogatives. The resolution passed by a vote of 225-201. All Republicans except for five of the most conservative voted for the resolution, and all the Democrats voted against it.

In The United States House of Representatives v. Burwell, the House as an institution alleged that the Executive Branch had specifically usurped the powers of the Legislative Branch by shifting money from one account to another without specific Congressional authorization. Speaker Boehner’s position was that while the Courts had ruled individual Members of Congress did not have the standing to sue, it could not deny that the entire House of Representatives suffered an injury when its very specific constitutional appropriation powers had been infringed by another branch of the government.

As we wrote in 2016:

The House of Representatives sued the Executive Branch—Secretary of Health and Human Services Sylvia Burwell and Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew, to be precise—alleging that the Administration has spent money that Congress did not provide to carry out the provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA, or Obamacare). The U.S. Constitution permits money to be spent if and only if it is appropriated by a bill passed by Congress. If Congress did not actually provide the money for such payments, the Executive Branch would have misappropriated to itself the Legislative Branch’s rights to appropriate (spend) funds. As a result, the House of Representatives voted to file suit against the Obama Administration to block the funds in question from being spent.

This is the crux of U.S. House of Representatives v. Burwell: When Congress passed Obamacare, did the legislature also actually provide funds to make payments to insurance companies to help keep costs low for consumers? Both the Administration and the House agreed that Congress authorized the government to make payments when it passed Obamacare. But authorizing is only one half of the spending equation. The two branches of government disputed whether Congress actually went a step further and appropriated the funds to do so, and the House maintains that the payments made since January 2014 have been given without its approval. The Court agreed with the House, and in a May 12, 2016, decision issued by U.S. District Judge Rosemary M. Collyer, it defended Congress’ “power of the purse” and its legislative prerogatives more generally.

In the past, when individual Members of Congress or groups have filed suit against the Administration alleging violations of their constitutional prerogatives as legislators, courts typically have ruled that they lack standing to sue. However, according to the Rules Committee report on the resolution, adopting it would signify the House’s approval of the lawsuit, and a “House of Congress is the natural and appropriate plaintiff to urge the courts to enforce the separation of powers.” The Obama Administration sought to have the case dismissed, arguing that the House lacked standing to sue, but Judge Rosemary Collyer of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia ruled that the “constitutional trespass alleged in this case [spending without an appropriation] would inflict a concrete, particular harm upon the House for which it has standing to seek redress in this Court.”

Naturally, the Obama Administration appealed Collyer’s decision. Later that year, Donald Trump was elected President, and his Administration initially continued the appeal. However, the Administration and the House eventually came to a settlement obviating the need for additional litigation. In the settlement, though, the Executive Branch asserted that it “continues to disagree with the district court’s…conclusion that the House had standing and a cause of action” to sue. Thus, neither the Court of Appeals nor the Supreme Court ruled on the case.

The 2018 mid-term elections yielded another period of divided government when the Democrats took the House majority in January 2019. This, too, resulted in another House lawsuit. In 2019, in U.S. House of Representatives v. Mnuchin, et al, the House tried to block an Executive Order by President Trump, who tried to build the border wall with funds appropriated for other purposes. Speaker Pelosi, who had opposed the original House action, decided that maybe it wasn’t such a bad idea after all.

On April 4, 2019, the House’s Bipartisan Legal Advisory Group (BLAG) voted 3-2 to authorize the lawsuit. The BLAG is a panel consisting of the Speaker, the Majority and Minority Leaders, and the Majority and Minority Whips. According to the Standing Rules of the House, this group “speaks for, and articulates the institutional position of, the House in all litigation matters” (Rule II, clause 8(b)). In this case, the Democratic members of the BLAG (Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Majority Leader Steny Hoyer, and Majority Whip James Clyburn) voted to allow the lawsuit, and the Republican members (Republican Leader Kevin McCarthy and Republican Whip Steve Scalise) voted against it. The day after the BLAG’s vote, the House General Counsel filed a complaint with the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia.

According to the House’s complaint, the Trump Administration violated the Appropriations Clause of the U.S. Constitution. The Appropriations Clause (Article I, section 9) states that “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law”. It claims that Congress duly appropriated only $1.375 billion for “barrier construction,” but that the appropriations for the additional monies the Administration is using are for other purposes, not for building a wall. Though the District Court said the House could not sue, the Court of Appeals ruled that the House could sue the Executive Branch.

So the policy of the House claiming standing in Court to oppose efforts to infringe on its constitutional powers has been used by both parties.

On What Grounds Could the House Challenge the Constitutionality of the Student Loan Forgiveness?

Assuming the House has standing to challenge the loan forgiveness plan, it could attempt to argue that the President overstepped his authority on a couple of grounds.

The House could argue that the student loan forgiveness plan violates the “major questions” doctrine, which states that the Executive Branch may not make significant policy decisions that rightfully belong to Congress. Earlier this year, in EPA v. West Virginia, the Supreme Court struck down an EPA regulation on the grounds that it violated the major questions doctrine. In the Court’s opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts explained, the major questions doctrine “took hold because it refers to an identifiable body of law that has developed over a series of significant cases all addressing a particular and recurring problem: agencies asserting highly consequential power beyond what Congress could reasonably be understood to have granted.”

A problem for the Administration is that the action is “beyond what Congress could reasonably be understood to have granted.” The Administration based its legal justification for this action on the Higher Education Relief Opportunities for Students Act of 2003 (P.L. 108-76). A Department of Justice memo justifying the action says that the law “vests the Secretary of Education…with expansive authority to alleviate the hardship that federal student loan recipients may suffer as a result of national emergencies” and that the covid pandemic qualifies as a national emergency. However, it stretches credulity to say Congress intended the bill to be used this way. The first section of the act, which was passed during the Global War on Terror, makes it clear that it was intended to aid military personnel and their families. Hence the acronym for the law, the “Heroes Act.” By contrast, the Administration’s action benefits a much wider group of the population. Additionally, the House passed it 421-1 via a suspension of the rules, and the Senate passed it via unanimous consent. The way the HEROES Act passed indicates that it was non-controversial. There can be no doubt that a student loan forgiveness plan would have engendered much more debate than the HEROES Act did. Furthermore, the discussion of student loans is fraught with ethical and policy questions—some of which were suggested in the introduction—and different policies will come with various trade-offs. The proper authorities to make such determinations are the people’s representatives in Congress, not the Executive Branch. So a challenge to President Biden’s plan on the grounds that it usurps legislative power may have some heft to it.

The major questions doctrine suggests that Congress did not intend to give the Executive Branch the power to make such a sweeping act of loan forgiveness. Therefore, Congress did not provide the means either, which is to say it did not appropriate the funds for these loans with the intention that they would be forgiven in this way. Since the funds were used in such an unanticipated way, the House could argue that it is a violation of its prerogative to appropriate. The Constitution specifically reserves to Congress the right to appropriate money: “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law…” (Article I, Section 9). In this sense, the House could argue that President Biden’s policy is not a loan “forgiveness” as much as it is a transfer of accounts payable to the student loan program to the general funds and, in reality, to the national debt of the United States. So notwithstanding the nominal appropriations for the loan programs, Congress did not intend them to be used that way.

The Political Situation in the House Today

Options for Members who are upset over the student loan forgiveness plan are limited since the Democratic majority would not vote to sue a Democratic Administration. One option for the House Republicans is that they wait until after the election and, if they win the majority, move to file suit against the Administration.

Or, they can introduce a resolution authorizing a lawsuit right now, along with a subsequent discharge petition, to force a vote before the end of this Congress. Rep. Tim Ryan, a Senate candidate in Ohio, claims he is opposed to President Biden’s policy. Well, by signing a discharge petition, he and other Democrats in swing districts could put their money where their press releases are and force a vote before Congress adjourns for the year.

In addition to the challenge of succeeding with a discharge petition, another challenge to overcome is how the House would proceed with a lawsuit. Normally H.Res. 676 would easily serve as the template for a new resolution authorizing litigation on the House’s behalf. However, that resolution authorized the Speaker to intervene. Today, the House Republicans couldn’t introduce such a scheme since Speaker Nancy Pelosi—understandably—would not be the most effective agent for a House authorizing a lawsuit challenging a plan she praised.

Instead of authorizing the Speaker, the House could create an alternative scheme with the following elements:

- The resolution would create the ad hoc Bipartisan Constitutional Litigation Advisory Group (BCLAG), which would articulate the House’s position with respect to litigation concerning the Congress’s constitutional prerogatives this Congress.

- The BCLAG would be authorized to hire outside counsel to represent the House in matters affecting Congress’s constitutional prerogatives. The BCLAG would be authorized to direct the outside counsel to file a lawsuit where a constitutional trespass is alleged.

- The Speaker, the House’s Bipartisan Legal Advisory Group, and the House’s general counsel would be forbidden from intervening in matters affecting Congress’s constitutional prerogatives during the 117th Congress, except by order of the House.

- The BCLAG would be composed of the chair and ranking minority members of the Committee on the Judiciary and the Committee on Oversight and Reform and the sponsor of the resolution, who would chair the group. (It may be unseemly for a resolution creating a panel to name its sponsor as chair—fair point, though it does allow the minority a way to control the process. Also, a practice of the early House, which has long fallen into disuse, was that the person who moved for the creation of a select committee was customarily named its chairman.)

Congress must act quickly to pass a discharge petition and vote to file suit against the Biden Administration before this becomes solely a campaign issue. If the moderate Democrats expressing opposition to the President’s policies do not sign the discharge petition, it may well be that the only way the Biden policy can be stopped is by electing a Republican majority it the House, who, on January 3, can pass a similar motion to the one the Republican majority passed in 2014.