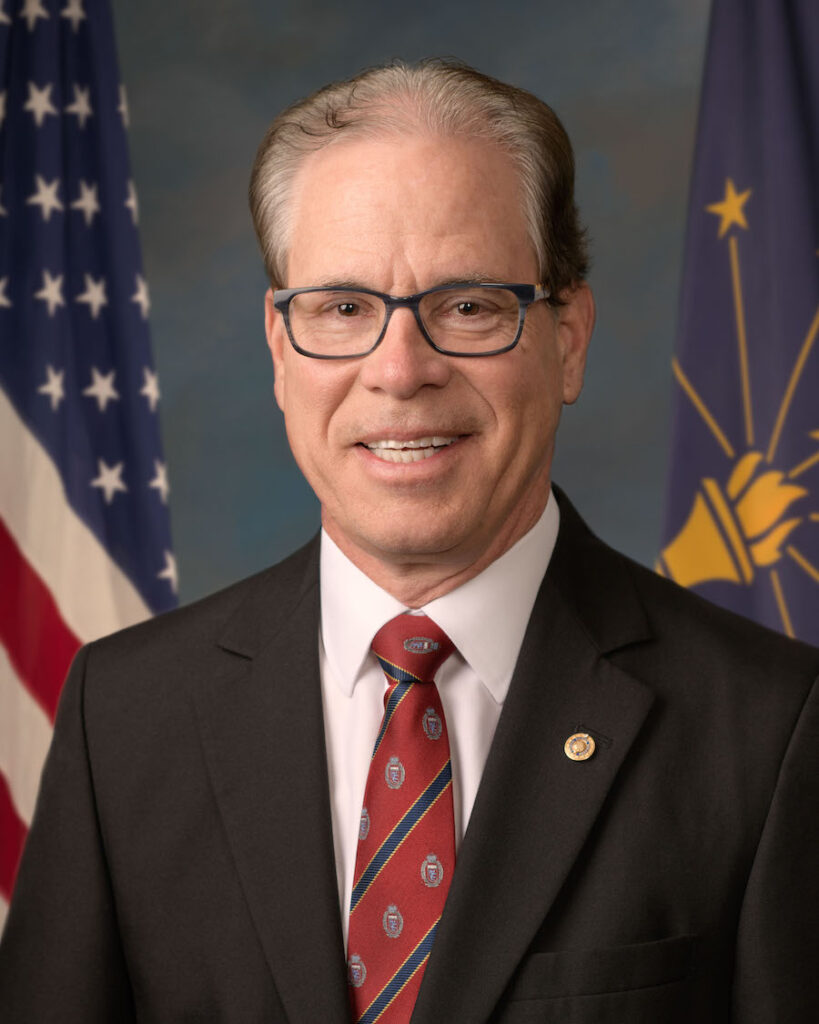

Earlier this year, the Department of Labor issued an emergency rule requiring employers to mandate that workers be vaccinated against COVID-19 or undergo regular testing and wear a face mask. This rule was highly controversial, as it imposes significant requirements on the private sector that could cost hundreds of thousands of people their jobs. To attempt to overturn this Executive Branch rule, the Senate Republicans, led by Senator Mike Braun, the ranking member of the Employment and Workplace Safety Subcommittee of the Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, have advanced a disapproval resolution under the Congressional Review Act.

A disapproval resolution is a joint resolution halting the policy or action of the President or other Executive Branch official. Joint resolutions must pass both Houses of Congress and must go to the President for his signature. If the President vetoes the joint resolution, Congress may attempt to override it.

While Congress can consider disapproval resolutions for various Executive actions, the Congressional Review Act provides special procedures for the expediting disapproval resolutions nullifying Executive Branch regulations specifically. Additionally, if such a disapproval resolution is enacted, the regulatory agency may not issue a similar rule in the future.

Why are Congressional Review Act (CRA) joint resolutions special?

Congress enacted the Congressional Review Act in 1996 to strengthen Congress’ hand in striking down Executive Branch regulations. It provides special procedures to speed up the consideration of disapproval resolutions nullifying regulations. As we explained in late 2016,

The law provides that an agency must notify Congress whenever it issues a regulation, and a Member has 60 days to introduce a joint resolution of disapproval. (Excluded from this period are days when either the House or Senate is adjourned for more than three days.) In the Senate, such a resolution is not amendable, debate is limited to 10 hours, and it cannot be filibustered.

Additionally, the CRA provides for special procedures to advance a joint resolution when it is stuck in committee in the Senate. When a joint resolution is introduced, it is referred to the committee with jurisdiction over the subject matter of the agency rule in question. In the Senate, if the committee has not reported the joint resolution 20 calendar days after the rule is submitted to Congress or it is published in the Federal register, it may be discharged if a group of 30 Senators present a petition. The provision of the Congressional Review Act allowing for the discharge petition affords the minority a significant advantage and allows them to move the joint resolution along when they normally wouldn’t be able to do so.

If a committee reports it or if it is discharged, a motion to proceed to consider the joint resolution is in order. Normally the motion to proceed to a piece of legislation is debatable and can be filibustered; however, the motion to proceed for joint resolutions under the Congressional Review Act are not debatable. Once a Senator makes a motion to proceed, the Senate votes on the motion immediately. If the motion succeeds, the Senate debates the joint resolution itself and votes on it when the time for debate expires.

When is the Congressional Review Act most effective?

The Congressional Review Act is most effective when a new President is of a different party from his predecessor and his party also controls Congress. In those cases, Congress is undoing the previous President’s regulation, so there’s little chance of a veto when the Congress sends the new President a disapproval resolution. Since the Congressional Review Act became law, each time a new President has taken office, his party has controlled Congress. When George W. Bush took office, Congress enacted one disapproval resolution. When Barack Obama took office, the Democratic Congress enacted none. When Donald Trump took office, the Republican Congress enacted 16. The Democratic Congress has already enacted three disapproval resolutions this year.

If the Congressional Review Act is most effective for the majority in a unified government, why is the vaccine mandate joint resolution different?

Normally, when one party controls both Chambers and the White House, it’s a symbolic gesture for a minority party Member to introduce a congressional disapproval resolution, and they don’t go far at all. However, on November 17, Senator Mike Braun of Indiana introduced a disapproval resolution, S.J. Res. 29, to nullify the Biden Administration’s rule mandating COVID-19 vaccination and testing. All 50 Republicans, along with Democratic Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia, co-sponsored the joint resolution. All these Senators, along with Democratic Senator Jon Tester of Montana, voted for the legislation, which passed the Senate 52-48 on Wednesday, December 8.

Senator Mike Braun (R-IN), the ranking member of the Employment and Workplace Safety Subcommittee of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, led the effort to disapprove the Biden Administration’s vaccine mandate (Photo: Office of Sen. Braun)

Prior to the vote on the joint resolution, the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions did not vote to report the joint resolution. Instead, Senator Braun filed a petition to discharge the Committee from further consideration of the measure. Unlike the Senate’s typical practice of having the Majority Leader make the motion to proceed, Senator Braun made the motion. (Doubtless Senator Braun was not preempting other Senate business and this was worked out by the parties in advance. It is not without precedent for the minority to bring up a disapproval resolution per an agreement with the majority. For instance, in November 2011, the Senate considered S.J. Res. 6 per a unanimous consent agreement. Whether or not the majority party leadership agrees with a given disapproval resolution, coming to an agreement on bringing them up benefits the majority since it allows for predictability in scheduling Floor activities. Since the motion to proceed in this case can’t be filibustered, it’s possible that the leadership could lose control of the Floor in a Senate where there’s a slim majority and some majority Senators support the disapproval resolution.)

What will happen to S.J. Res. 29 in the House?

House Members often complain that the Senate is a legislative graveyard where all their legislation is quietly buried. In this case, the Senators who voted for the joint resolution will very likely have reason to complain that the House is a legislative graveyard.

In the House, the Speaker and majority leadership have immense power over the legislative agenda and the minority has very little. There’s little reason for Speaker Nancy Pelosi, a Democrat, to bring to the Floor a joint resolution overturning a Democratic Administration’s rule, so S.J. Res. 29 won’t go very far at all.

One way around the Speaker would be for a Member to introduce a special rule providing for debate and a vote on the joint resolution. The resolution would then be referred to the Committee on Rules. Then, after a layover period, opponents of the Biden Administration’s rule could then file a discharge petition to discharge the Rules Committee from further consideration of the special rule. A successful discharge petition requires 218 signatures, and if the motion is agreed to on the Floor, the House would vote on the resolution. Although the Republicans have a very strong minority, it is incredibly difficult to get even sympathetic members of the majority to sign a discharge petition since it effectively gives the minority control over the House Floor for a time. Even Democrats who oppose the vaccine mandate would think not just twice, but three or four times before crossing party leadership like that, so it is doubtful that such a tactic will work.

S.J. Res. 29 will in all likelihood wither away at the Speaker’s desk in the House, but it remains an important symbolic victory since it passed the Senate.

What other disapproval resolutions has the Senate considered this Congress?

The Senate has considered three other disapproval resolutions, each of which nullified a Trump-era regulation.

Senator Patty Murray introduced a joint resolution, S.J. Res. 13, created by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Senator Martin Heinrich introduced S.J. Res. 14, which rolled back an Environmental Protection Agency rule governing oil and natural gas standards. Senator Chris Van Hollen introduced S.J. Res. 15, which nullified a regulation by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency regarding national banks and federal savings associations.

The committees with jurisdiction over these joint resolutions were discharged from further consideration of them via the petition process provided for in the Congressional Review Act.

After the Senate passed each of them, the House passed each as well and President Joe Biden signed them earlier this year.

Strictly speaking, any Senator can make a motion to proceed, but by tradition, only the Majority Leader or his designee makes it, so the Majority Leader can set the Senate’s agenda. This year, two of the three joint resolutions that have passed both the Senate and House were brought up because the Senator who introduced the disapproval resolutions made a motion to proceed.