President Joe Biden started his first day in office by signing 17 Executive actions that range from Covid-19 to immigration to climate change and other domestic issues (at this writing, he is up to 45). To understand the meaning of these actions and their implications, it is essential to understand an Executive action’s definition. An Executive action is a tool that the President uses to set policy while carrying out the law. These actions, which can take the form of Executive orders, proclamations, National Security Directives, and other measures, can be used to set policy. Still, they are by no means equivalent to laws passed by Congress.

While somewhat excessive, President Biden’s Executive actions in his first day in office are hardly unusual. For instance, President Reagan revoked 39 Executive orders signed by his predecessor President Jimmy Carter, immediately after taking the oath. An Executive action is consequential, but it cannot be regarded as powerful as a piece of legislation signed into law. It is necessary to understand the American political system to understand why this is the case.

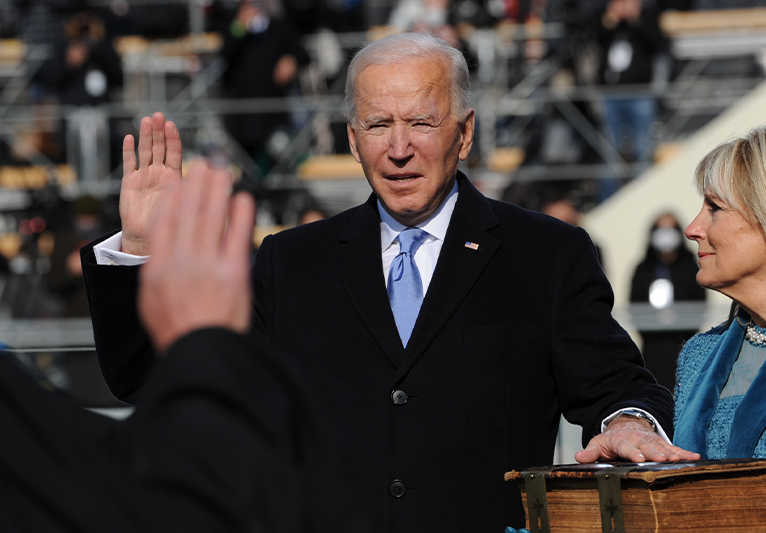

As the head of the Executive Branch, a President takes the oath to “faithfully execute the laws of the United States.” According to the Constitution, the President does not create laws, only signs and executes the law passed by Congress, the Legislative Branch. Furthermore, a President must share power with the legislators and the Judiciary Branch to govern the country. It is as simple as that. At least the theory is. The practice has shown that the act of governing is more complicated. The Executive Branch has grown in power over time because the Legislative Branch has given away its power and because the Executive Branch has developed powerful instruments to use when trying to carry out their political priorities.

Executive actions are effective while the person who signed them is in office, but the next President can easily rescind them. That is because a President cannot make laws but can only execute laws passed by Congress. The Constitution does not explicitly mention Executive actions like Executive orders, and they have evolved over time. They became more structured since the late 1800s, beginning with President Ulysses Grant. Presidents Herbert Hoover and John F. Kennedy were heavy users of Executive actions. But they are not legislative processes passed by Congress and signed into law by the President.

Nonetheless, without a doubt, Executive actions can be incredibly significant. President Abraham Lincoln used an Executive order to establish a military court in Louisiana to enforce the Emancipation Proclamation. Franklin D. Roosevelt used an Executive order to incarcerate Americans of Japanese descent during WWII. John F. Kennedy used an Executive action to create the Peace Corps. The list can go on, but the main point is that an Executive order can produce pseudo-legislative effects while the person who signed it remains in office. Once there is a change of presidents, since an Executive action is not a law, the new President can simply get rid of it.

That’s precisely what happened with the 45 Executive actions signed by President Biden so far. President Biden gave an obvious signal of wanting to reverse many of President Trump’s Executive actions. So, many of those Executive actions signed by President Biden are an unhindered rebuke to his predecessor. However, making his policy goals more durable will require congressional action. Nonetheless, with the stroke of a pen, he highlighted his priorities and his political agenda and took steps to implement them.

There are significant implications for foreign affairs issues with several of these Executive actions. Some, such as Executive actions to restore funding for abortion in third world countries and rejoin the United Nations Commission on Human Rights as an observer, will stir controversy within the United States.

But the two most key issues we will focus on here deal with two significant international agreements that involve American allies as well as strategic rivals – The Paris Accord on Climate Change and the re-entry of the U.S. into the World Health Organization (WHO). Signing an Executive action rejoining the Paris Accords and another rescinding the United States’ withdrawal from the WHO brought a feeling of relief to many U.S. allies. But this feeling of relief can turn back into anxiety under a future President.

According to the United Nation’s description, the Paris Agreement is a “legally binding international treaty on climate change.” It has 196 signatory countries that ratified the agreement as a treaty, with the legal consequences of a treaty. But the United States did not ratify the Agreement as a treaty. President Obama used an Executive action to commit the United States to the Agreement. So rather than committing the United States to the Agreement as a treaty would do, President Obama merely committed his own Administration to carry out the provisions agreed to by the other signatories.

Ratifying a treaty requires the approval of two-thirds of the Senators, which is the same high standard for proposing a Constitutional amendment. President Obama did not want to expend the political capital required to achieve ratification in the Senate, knowing he might suffer an embarrassing political defeat. As a result, the Paris Agreement was never submitted for a real debate before Congress since it was not regarded as a treaty. To be sure, the opposition to the Agreement in Congress was significant. But forcing Congress to debate and vote on a Treaty openly, would have put Senators on the record and made them accountable to their constituents on the issue of climate change. Even if the Paris Agreement was defeated initially, President Obama could have campaigned on the issue and attempted to ratify the treaty again after the voters had a chance to react to their Senator’s vote. Treaties are frequently resubmitted for ratification, multiple times, as evidenced by the United Nations Law of the Sea Treaty, which the Senate has never ratified.

Through an Executive action, joining the Paris Agreement was as easily undone by President Trump, who was under no obligation to continue his predecessor’s Executive action. Now, thanks to President Biden’s Executive action, the United States is back in. It is easy to see how the world is confused by American actions since it is like watching a tennis match – with compliance depending on which side of the net controls the presidency. However, the country’s rejoining of the Paris Agreement is still not as secure as if it were done by ratification.

As long as the Biden Administration will not submit the accord to Congress as an international treaty, American compliance will remain as precarious as before, creating uncertainty for companies and state and local governments trying to develop long-term plans to protect the environment. The 196 countries legally affected by this accord might be relieved by President Biden’s Executive action. Still, the international community should understand that the next President can very well withdraw the United States again four years from now. Had it been ratified by the Senate, only a two-thirds vote by the Senate could repeal it.

The Executive action retracting the United States’ withdrawal from the World Health Organization is another example of the same issue. On May 10, 2004, the United States became a signatory of the WHO, but it was never ratified as a Treaty. There are currently 168 signatory countries and 182 parties. That is the significant difference between the ratification of a treaty and non-ratification. The WHO is an agency of the United Nations. The United States has historically supported having an international body that can address global health threats, epidemics, pandemics, etc. A Pew Research Center study showed in 2020 that the public’s belief in the benefits of being part of the WHO was split. The United States has been the largest contributor to the WHO, amounting to 20% of the total contributions to its budget, until President Trump announced he would halt the contributions. But in 2020, only 46% of Americans had a favorable impression of how the WHO handled the Covid-19 pandemic, and only 59% of the population trusted the information coming from the WHO. With such a split in the public’s opinion, the historical American participation in shaping the WHO was barely even a significant domestic political issue.

For the international community and the traditional U.S. allies, President Biden’s Executive actions lowered the irritants in relations, particularly with our European partners, but it will be essential to watch the reaction of American public opinion. The American political system is very sensitive to accruing and dispensing power by any government branch. The public can revolt against this at the ballot box. To have a long-lasting effect, this Executive policy has to be translated into legislation. Executive actions are a powerful tool, but one has to hedge their bets that the same political party will win the presidency in four years. Of course, a President can gamble that the subject of an Executive action is so bipartisan that there is no political benefit for the next President attacking it or rescinding it. Yet, it’s a risk if your goal is lasting change rather than temporary political victories. President Biden’s statement that his Executive order tackling the climate crisis at home and abroad, signed on January 27, “makes it official that climate change will be at the center of our national security and foreign policy”, raised eyebrows. The Administration’s first actions, canceling the Keystone Pipeline with Canada and suspending federal oil and gas leases in New Mexico, has already caused considerable debate because of the loss of some 60,000 high paying jobs.

In addition to this, Gina McCarthy, the National Climate Advisor, agreed that the U.S. could meet the Paris accord targets “tomorrow” during the same press conference. In reality, the United States is well ahead of most other signatories in reducing carbon emissions. Yet, the Agreement has little value if other countries such as China and India do not meet standards similar to those established by the United States and Europe. To demand higher standards from the rest of the world, the United States should lead by ratifying the Paris Agreement into a treaty.

Another issue drawing international attention is whether the United States will rejoin the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), commonly referred to as the Iran deal. For all of the reasons we have dicussed here, joining the JCPOA by Executive agreement was a high-risk gamble by President Obama to make this agreement (and return billions of dollars to the Iranian regime), based on the hope that Hillary Clinton would succeed him. Unfortunately for President Obama’s plans, Donald Trump was elected in 2016 and proceeded to withdraw American support from the Iranian agreement. Unlike the Paris Agreement and rejoining the WHO, the Biden Administration will proceed more cautiously on this issue. The American Constitutional system requires that long-term, transformational change require legislative action. Achieving consensus is the key to incremental change in long-term American policy on critical domestic and international issues. Even if the words of a President sound louder than those of Congress, Congress’s actions are more permanent than those of Executive actions.