The Republicans have 50 Senators. The Democrats have 50 Senators. Who’s in charge? Who will actually run the Senate? The answer is that, unlike the House, the Senate votes on an organizing resolution negotiated by its leaders to determine who has what powers. For the last couple of weeks, Democrats have controlled the Senate, while Republicans have continued to hold committee chairs. That is because the Senate, being a perpetual body that always has a quorum (only one-third are up for reelection every two years), does not automatically reorganize at the start of a new Congress, but only after it passes the organizing resolution to reflect the new reality imposed by the last election.

Normally, this reorganization is uneventful since the majority party in a legislative body gets to call the shots on how it organizes its house, who chairs its committees, and the like. With an evenly divided Senate, the parties will share power instead—though the Democrats are technically in the majority, thanks to Vice President Kamala Harris. The sharp divide in the Senate will make the next two years challenging—and that can be a good thing, since the Senate should be a place to work through the issues that particularly bedevil the country.

How Legislatures Organize

How to Organize an Evenly Divided Senate

The Last Time the Senate Was Evenly Divided (2001)

Looking Forward to the Rest of This Congress

How Legislatures Organize

Modern legislative assemblies, whether it’s the U.S. Congress, the Canadian Parliament, or a state legislature, are incredibly complicated institutions, and the legislative process—the procedures and rules that legislators follow to enact laws—is also complex. To legislate, a house must have rules of procedure to govern debate. Additionally, modern legislatures have committee systems, staff, budgets, and other resources. Organizing a house is the process of putting all these details into place so that legislators can make laws. Organizing consists of tasks like setting rules, naming officers, creating committees, to name a just a few. Each assembly has a different process or organizing and houses commonly decide such matters by adopting one or more simple resolutions, which are usually passed by majority vote (unless a rule provides otherwise).

Since organizing a legislative assembly requires the assent of at least a majority of its members, the political party that controls most of the seats can typically organize the house. Today, both the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate follow this practice. Organizing the Chamber allows the majority political party to control the flow of legislation on the Floor, the committee system, budgets and other resources, and the like. Controlling these aspects of the legislative process allows a majority party to work its will and advance its agenda. Since the legislative success depends so much on these resources, when questions involving organization come up for a vote, at least the majority party votes for it. (Votes on controversial housekeeping or procedural resolutions will divide along party lines, whereas uncontroversial resolutions may be agreed to on a bipartisan basis.) Organizing the House or the Senate this way ensures that the majority party that they can control the Chamber for the duration of the Congress.

Although organizing the House and Senate benefits the majority party, the minority party still has some say and influence over the process. In contemporary practice, both the House and Senate committee resources, like seats on the panel, staff, and budgets, are allocated roughly proportionally to the number of members each party has in the chamber as a whole (though there are some exceptions). So, for example, if a party controls 55 percent of the seats in the chamber as a whole, it will control about 55 percent of the seats on a committee. The chamber’s party leaders negotiate the ratios for committee resources at the beginning of each Congress, and the House and Senate formalize these agreements after the new Congress opens on January 3 following a general election.

How to Organize an Evenly Divided Senate

Since organizing a Chamber is a partisan affair, with the majority party controlling the agenda, it might seem like a Senate with a 50-50 split would have no majority. In practice, even if both parties have an equal number of Senators, one party is the “majority” because of a particular provision of the Constitution. According to the Constitution, the Vice President of the United States is the presiding officer of the Senate, so she governs debate. It also provides that she does not have a vote, except in the case of a tie. Due to the Vice President’s right to cast a vote in the case of a tie, her party is considered the majority, since everyone, especially her party, expects her to vote along with the Administration and her party in Congress. Since the current Vice President, Kamala Harris, is a Democrat, the Democrats are considered the majority now.

Though the Democrats are in the majority due to Vice President Harris’ tie-breaking vote, a couple of elements of Senate procedure complicated this year’s the organization of the Senate. First, the Senate is an ongoing body whose rules do not automatically expire at the end of each Congress. Unless a resolution specifically includes an expiration date, they remain in place until another resolution supersedes them. One important aspect of Senate business that is governed by resolution is committee chairmanships, which also continue until new resolutions are passed. Thus, until the parties resolved the power sharing arrangements, Republicans technically served as the chairmen of the committees and did so until the Senate agreed to new resolutions nominating the Democrats to lead them. So, was a Senatorial wonder world where Republicans were in the minority but were chairing committee meetings. Some Senators said Republicans were chairs, some said Democrats were, some were not sure. “It’s kind of goofy at the moment,” said Republican Whip John Thune of South Dakota.

As a point of comparison, the topsy-turvy committee situation in the Senate would never be seen in the House of Representatives. At the end of a Congress, the House’s rules expire, so the new House convenes, it must pass various resolutions regarding their rules, chairmen, and the like. For example, Rep. John Yarmuth served as Chairman of the Budget Committee in the 116th Congress and continues to do so in the 117th Congress. Since the House rules expire each Congress, the House had to agree to a resolution naming him chairman this year, just as it did in 2019. Thus, in the House, you’ll never have Members remaining as chairmen even after their party is in the minority. The House’s parliamentary procedures simply do not allow for it, while the Senate’s perpetual nature does.

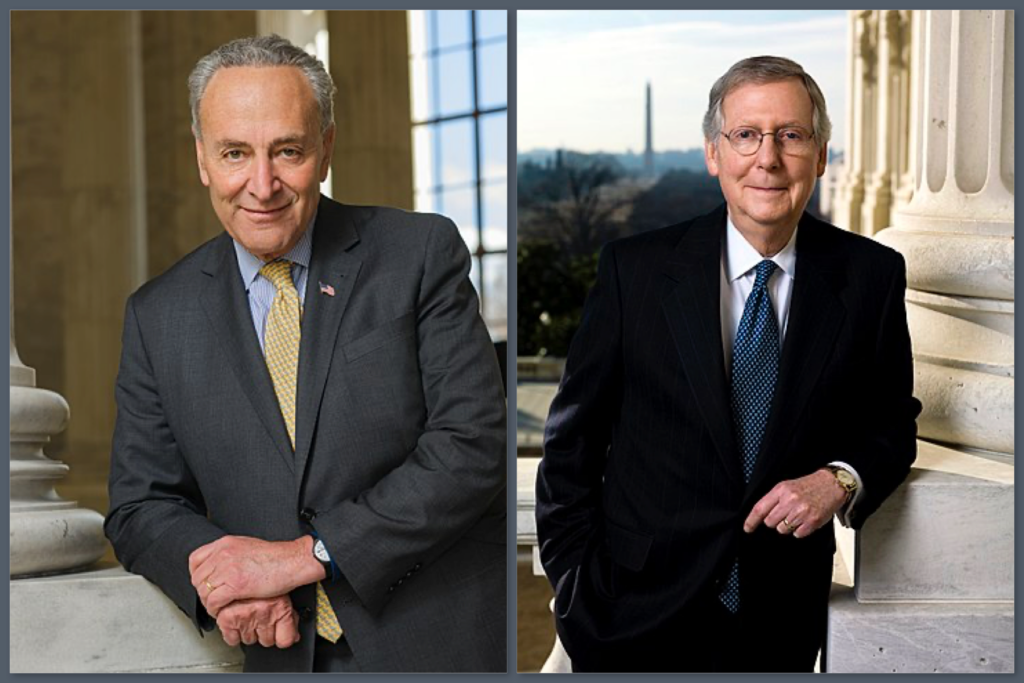

In addition to the Senate’s ongoing nature, the filibuster complicated the power sharing agreement. Senators may filibuster simple resolutions, so the Republicans could have filibustered any resolutions needed to organize the chamber. In fact, Republican Leader Mitch McConnell initially held out on finalizing an agreement…because of the filibuster (very meta, as they say). Since 2013, both parties, while in the majority, weakened the filibuster, so now all that remains of it is the ability for Senators to slow down or completely block legislation, rather than both legislation and nominations. McConnell wanted assurances from Majority Leader Schumer that the power sharing arrangement would protect the filibuster. Schumer flatly refused. McConnell, however, gave up his demands after two moderate Democrats, Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Senator Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, have publicly pledged to refrain from voting to eliminate the legislative filibuster. Neither Senator’s promise is binding upon them in any legal or procedural sense. Nor did their pledges change the text of the organizing resolution. Instead, McConnell is relying upon them to be true to their word. This resolution to the power sharing agreement impasse is very senatorial. One distinctive characteristic of the Chamber is that agreements or assurances, of varying degrees of informality, resolves a deadlock, and moderate Senators, like Sinema and Manchin, are often responsible for the breakthrough. The filibuster has been the subject of such agreements in the past too. So, the path forward on the power sharing agreement is much in keeping with the culture of the Senate.

The Last Time the Senate Was Evenly Divided (2001)

The power sharing agreement that is in place for this Congress was based on the agreement reached the last time the Senate had a 50-50 split. In 2001, twenty years ago, Senator Trent Lott of Mississippi, the Republican Leader, and Senator Tom Daschle of South Dakota, the Democratic Leader, had to find a way forward following the highly divisive 2000 elections. The general elections returned a 50-50 Senate for the 107th Congress, with the White House flipping from the Democrats to the Republicans. This case had a twist that made it even more unusual than today’s situation. In the 106th Congress, the Republicans held 54 seats, an outright majority. But they lost four seats in the election, so when January 3 came, the Democrats were the majority since the lame-duck Vice President Al Gore, a Democrat, gave them the tie-breaking vote. Yet everyone knew that the Republicans would be the majority less than three weeks later, when Republican Vice President Dick Cheney was inaugurated on January 20. Thus, on January 3, the Senate adopted a resolution simultaneously naming Democratic Senator Robert Byrd to be the President pro tempore until noon on January 20, and Republican Senator Strom Thurmond to that post beginning at noon on that date. On the same day, it agreed to a similar resolution naming Democratic chairmen until the George W. Bush Administration came to power, at which point Republican Senators would automatically become chairmen.

In addition to the resolutions naming the Presidents pro tempore and the chairmen, the Senate also agreed to a resolution divvying up committee seats and resources. On January 5, the Senate unanimously agreed to S. Res. 8, which formalized the accord that the party leaders had arrived at. S. Res. 8 provided that the seats on the committees would be divided equally between the two parties. Likewise, the budgets, staff allotments and meeting spaces were to be apportioned equally. Having equal numbers of Republicans and Democrats on the committees and subcommittees increased the likelihood of ties when voting to report legislation and nominations, so S. Res. 8 included provisions to ensure the Senate’s work could continue even if there were an unusually high number of ties. If a subcommittee tied, the chairman of the full committee was authorized to advance the measure to the full committee. If a full committee tied, the Majority Leader or the Minority Leader was authorized to make a motion to discharge the committee of further consideration of the measure after he had consulted with the chairman and ranking member of the committee. Debate on the motion was limited to four hours, so it could not be filibustered.

Another important provision of S. Res. 8 affected the cloture process. A cloture motion allows the Senate to vote to end debate, and if cloture is invoked, the rules limit Senators’ ability to amend legislation. Thus, to protect the Senators’ right to amend, S. Res. 8 prohibited cloture motions before 12 hours of debate had passed.

Importantly, S. Res. 8 provided that if either party achieved a majority during the Congress, the ratios agreed upon would automatically favor the new majority. During each Congress, vacancies often occur due to the death or resignation of one or more Senators, so it was entirely conceivable—perhaps likely—that one of the parties would gain overall control. In fact, in the 107th Congress, that happened—twice! In June 2001, Republican Senator Jim Jeffords of Vermont announced that he would become an Independent who would caucus with the Democrats. That tilted the Chamber to the Democrats, and they reorganized. In place of Republican Strom Thurmond, they elected Democrat Robert Byrd as the President pro tempore on June 6. On June 29, the Senate agreed to S. Res. 120, which readjusted the committee seat ratios to favor the majority party by one (with the exception of the Ethics Committee, which is always evenly divided). It also provided that no Senator would lose his or her seat on committees as a result of the change. Additionally, any agreements that Chairmen and Ranking Members had made concerning committee budgets and spaces were to remain in effect, unless the two committee leaders renegotiated them.

The second change in the Senate majority of the 107th Congress came in 2002. In October, Senator Paul Wellstone, a Democrat from Minnesota, died and Governor Jesse Ventura, an Independent, selected Dean Barkley, also an Independent, to replace him until the state elected a successor. Both Majority Leader Tom Daschle and Republican Leader Trent Lott lobbied Barkley to join their party organizations. President George W. Bush did as well, inviting Barkley to the White House, even though he was to be in office for only six weeks. Around the same time, there was a special election to fill the seat of the late Senator Mel Carnahan, who had been elected to the Senate posthumously. In the special election, former Representative Jim Talent, a Republican, defeated the temporary appointee, Senator Jean Carnahan, the widow of Senator Mel Carnahan. (In a nod to how important a swing vote in an evenly divided Senate is, Barkley joked that he wanted Carnahan to win, so he could have remained “the balance of power” for his entire six weeks in office.) With Talent’s victory, the Republicans once again had a numerical majority, but it was in the final few days of the 107th Congress and they did not bother to reorganize the Chamber.

Looking Forward to the Rest of This Congress

On Wednesday, February 3, the Senate unanimously agreed to S. Res. 27, which codifies the power sharing agreement. It is substantially the same as S. Res. 8 of the 107th Congress, with only minor technical differences that do not affect how it operates. Also, it agreed to resolutions putting majority and minority members on committees—formally allowing the Democrats to take control of the chairmanships—and electing a Democratic Secretary of the Senate.

In addition to adopting these resolutions, Majority Leader Schumer and Republican Leader McConnell engaged in a dialogue about how they would lead their parties and the Senate for the rest of the Congress. Schumer pledged to open the amendment process, by refraining from “filling the amendment tree,” a practice whereby the Majority Leader introduces several essentially meaningless amendments that prevent other, substantial amendments from being considered. It’s a practice that has increased over the past few decades, to the detriment of the Senate’s open amendment process. “I am…opposed to limiting amendments by ‘filling the tree’ unless dilatory measures prevent the Senate from taking action and leave no alternatives…That is how we will operate in the 117th Congress under the new Democratic majority,” Schumer said.

Complementing Schumer’s commitment to an open amendment process was McConnell’s commitment to limit debate on the motion to proceed. The motion to proceed is a way the Senate begins debate on a piece of legislation or other business. The motion is debatable, so it’s known as a “debate on the debate.” And since it’s debatable, it’s also an opportunity to filibuster. McConnell noted that Senators extend debate on the motion to proceed so that they can get guarantees to ensure their amendments are considered. He said that Schumer’s commitment with respect to amendments “should help in alleviating the practice” of lengthy debate on the motion.

The Schumer-McConnell colloquy about amendments and the motion to proceed set a positive tone for the rest of the Congress. It also carried a risk: Schumer could engage in the practice of filling the amendment tree if he perceives the Republicans engaging in “dilatory measures” and McConnell could endorse a strategy of extending debate on the motion to proceed if he thinks the Democrats have shut down the amendment process. Retreating from their stated intentions would sour the relations between the parties and make legislating more difficult. Let’s hope they avoid that by keeping debate open, constructive, and collaborative.

The durability of the Schumer-McConnell accord on debate norms will probably be tested at some point during the Congress, but when, we don’t know—hopefully later rather than sooner. It’s also an open question as to how long S. Res. 27 itself will be needed. As the example of the 107th Congress suggests, we may see another reorganization of the Senate this year or next, but that is almost impossible to predict since it depends on which seats become vacant and how they are filled.

Another forward-looking question is what effect the 50-50 breakdown will have on the pace of legislation going through the Chamber. It is reasonable to think that the 50-50 split will slow down legislation. If legislation makes it to the Floor, the Democrats need not fear tied votes, so they need not fear a deadlock. Rather, the 50-50 split will make ending filibusters more challenging. Ending debate on legislation requires 60 Senators to vote for cloture. Given the party divisions, the Democrats will need to coax 10 Republicans to vote to end debate. That’s a heavier lift than most Senate majority parties need to accomplish. And they need to do that without losing any Democrats, who might be dissatisfied with concessions made to the Republicans. Given the heightened challenge of overcoming filibusters, there will still be considerable pressure on the Democrats to eliminate the practice, despite Senator Manchin’s and Senator Sinema’s assurances that they would not vote for it.

It is way too early to tell whether the filibuster will be entirely eliminated this Congress, or whether creative partisans will come up with an alternative that effectively does an end run around the filibuster by using a budget reconciliation process on steroids (more on that in the future). It’s also too early to predict how everything else will shake out. Right now, we’re faced with a rather rare parliamentary situation that will test the parties’ abilities to work together to benefit all Americans. Yet finding consensus is exactly what the Senate is supposed to do. May the current Senate exceed everyone’s expectations.