The coronavirus pandemic has led some to call on Congress to continue its operations while Members are dispersed throughout the country. H.Res. 965 authorizes the Speaker to allow Members to vote by proxy when the Sergeant-at-Arms notifies her that there is a public health emergency due to the coronavirus. Conceivably, this means that a only minority of the Members will be present in the Chamber when conducting business. On the face of it, that would violate Article I, Section 5, of the Constitution, which requires a majority of Members to do business. To get insulate the votes against constitutional challenges, H.Res. 965 stipulates that proxy votes would count towards a quorum. This, however, would still seem to violate the intent of the Framers of the U.S. Constitution.

What does the Constitution say about quorums in Congress?

Article I, Section 5, of the U.S. Constitution sets forth a requirement that a majority of the Members of either House of Congress must be present for it to conduct business:

Each House shall be the Judge of the Elections, Returns and Qualifications of its own Members, and a Majority of each shall constitute a Quorum to do Business; but a smaller Number may adjourn from day to day, and may be authorized to compel the Attendance of absent Members, in such Manner, and under such Penalties as each House may provide.

(Article I, Section 5)

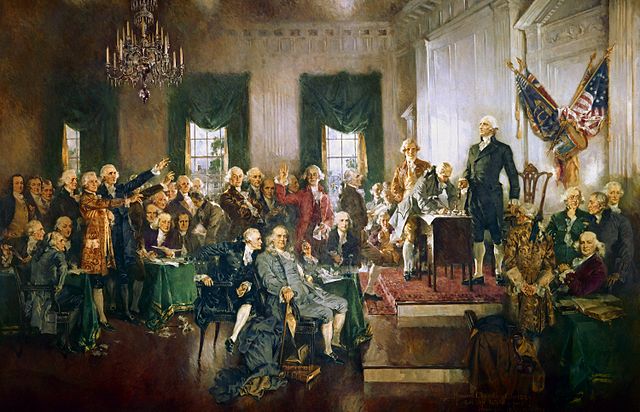

What did the delegates to the Constitutional Convention say about the quorum?

The current form of the quorum clause was the subject of debate at the Constitutional Convention of 1787.

The Committee of Detail was a group of delegates entrusted with devising a draft constitution that reflected the delegates’ agreements. On August 6, 1787, it reported a draft that said “a majority of members” would “constitute a quorum to do business,” though “a smaller number may adjourn from day to day.” Unlike the Constitution that was ratified, the Committee of Detail did not include a provision allowing for the “smaller Number” to “compel the Attendance of absent Members” or penalize those who were missing.

On August 10, the delegates debated the Committee of Detail’s quorum requirement. Two important concerns emerged. If the quorum were too high, it could prevent the majority from being able to transact business. If it were too low—or could be manipulated to be lowered—it would allow a small group of people to impose their will upon others.

According to James Madison’s Notes of Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787,some delegates advocated granting the Legislature complete or partial discretion in setting a quorum:

- John Francis Mercer of Maryland proposed following the example of Great Britain, where Parliament could determine its own quorum. There, he said, “the requisite number is small & no inconveniency has been experienced.”

- Gouverneur Morris of New York proposed setting the quorum at 33 Representatives and 14 Senators. This would initially be a majority for each Chamber, though it would be less than a majority as Members were added. Congress, he thought, should have a relatively low quorum since it would prevent a small group of people from withholding a quorum, which would be a particular risk when “a particular part of the Continent may be in need of immediate aid.”

- Rufus King of Massachusetts proposed initially setting the quorum at 33 Representatives and 14 Senators, but allowing Congress to increase the numbers as it saw fit. As the number of Members increased, a majority quorum would be “cumbersome.”

Other delegates feared that a low quorum would allow small groups to make laws for the rest of the country:

- Elbridge Gerry, also of Massachusetts, proposed that for the House the quorum should be no less than 33 and no more than 50, with the Legislature free to select a number within these bounds. A quorum of 33 in the House, Gerry said, would allow as few as two states to make laws for the rest.

- George Mason of Virginia said the majority quorum provision was a “valuable & necessary part of the plan.” In fact, he was concerned that a mere majority would allow people to object to the plan as a whole. He reasoned that with a lower quorum, states closer to the seat of government could make laws favorable to themselves in the absence of more distant states. “If the Legislature should be able to reduce the number at all, it might reduce it as low as it pleased & the U. States might be governed by a Juncto,” he said.

The delegates considered and overwhelmingly rejected King’s motion that the Constitution set a minimum of 33 Representatives and 14 Senators while the number to be increased by law. Only the Massachusetts and Delaware delegations favored King’s plan.

James Madison and Edmund Randolph, both of Virginia, moved to amend the draft by inserting a provision allowing for each House to summon and penalize absent Members. All the state delegations except for Pennsylvania supported this amendment. In fact, the Pennsylvania delegation was divided on the question. Then the delegations unanimously approved the majority quorum provision, as amended, and it is this version that made its way into the U.S. Constitution.

Would proxy votes satisfy the constitutional requirement for a quorum?

It is clear that the delegates considered the possibility of quorums of consisting of a minority of the Members and rejected this option in favor of a majority quorum. That is beyond dispute. What is disputed is whether proxy votes counting towards a quorum would pass constitutional muster. Even though the Constitution allows each House to determine its rules of procedure (Article I, section 5), proxy votes counting towards quorum seem to run contrary to the intent of the delegates at the Constitutional Convention.

Proxy voting was certainly possible in the time of the Constitutional Convention. For instance, absentee or proxy voting was not unknown in the colonies. Yet, apparently, the suggestion was not raised at the Convention. One should be careful not to infer too much from silence, but one possibility is that the delegates did not consider that the Congress would ever “meet” by proxy. In fact, proxy voting would have settled some of the problems delegates on both sides of the issues raised. If proxy voting were permissible, then the distant states could have more easily defended themselves by stationing a member at the capital, armed with proxies of their absent colleagues. By the same token, those who feared that a small number could obstruct business by collecting proxy votes from others who shared their concerns. No one, apparently, raised proxy voting as a solution for issues with the quorum; rather, both sides seemingly operated under the assumption that a physical presence was necessary for participation in Congress.

If proxy votes were to count towards a quorum, the Randolph-Madison amendment would be a redundancy. Since the amendment allows each House to “compel the Attendance of absent Members,” it is predicated on the notion that a physical presence is necessary for Congress to conduct its business. If a physical presence were not necessary, it would be unnecessary to “compel the Attendance of absent Members.” Nor would there be any reason to penalize them for failing to show. However, the states nearly unanimously voted to include this provision in the Constitution, highlighting the importance of a physical presence at the Constitutional Convention.

The Framers’ concern over the dangers of small numbers of Members of Congress transacting business in the absence of the majority of their colleagues is as valid today as it was in 1787. It is true that the coronavirus pandemic presents great difficulties to Congress, and both Chambers have shown that they can still conduct business without violating constitutional safeguards. As much as Congress needs to look to the here-and-now, it also must look to the future. In the long-run, the in-person presence of Members of Congress is absolutely vital to the strength of the Legislature, and no amount of proxy votes may substitute for it.